BY MARY GREGORY

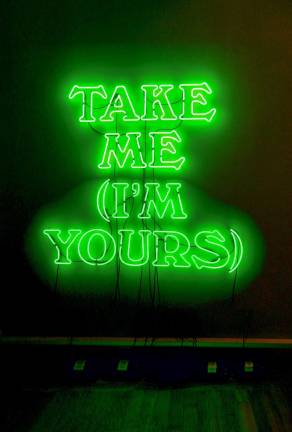

How can you start a serious art collection on a budget? The Jewish Museum hopes you’ll take up their offer in the ambitious, thought-provoking, fun and memorable exhibition “Take Me, I’m Yours,” and take some home for free.

Forty-two artists from around the world are participating, offering works they hope will spark serious discussion that will carry beyond the walls of the museum, as will the works themselves. Start your visit with one of Ian Cheng’s and Rachel Rose’s fortune cookies packed with pithy, sometimes politically charged messages, then take a bag from the wall, a gallery guide from the cleverly repurposed paper-towel dispenser, and head inside to look at, touch, think about and ultimately love or leave behind any of the works in the show. They’re all there for the taking.

Other than the playful freedom of interacting with artworks in a museum, which is refreshing and exciting on its own, the show addresses countless conceptual, societal and political realities. First on the list is why does art have to be precious and elitist? These artists are putting their money where their mouths are, saying emphatically that it doesn’t. Challenging the commoditization of art is particularly surprising considering that these are canonical artists, like Gilbert & George and James Lee Byars, whose works often command astronomical prices.

Besides the democratization of art, the exhibition also speaks to the vision of the Jewish Museum itself. Jens Hoffmann, director of special exhibitions and public programs, explained, “I think every museum is part of a community, or if you will, every museum is a community. And part of a community — particularly in Jewish tradition — is the idea of giving and sharing. It’s very fundamental. So in this case, we’re really giving and sharing, not only ideas, but we’re also giving and sharing the artworks that are on display.”

For a brief time, the museum, rather than protector or collector, has become the distributor of art.

The exhibition is based on one that took place in 1995 in London’s Serpentine Gallery. It was conceived of by artist Christian Boltanski and Hans Ulrich Obrist, then director of the gallery. They’re both on board again for this iteration. Obrist worked with Hoffmann and Kelly Taxter, associate curator, to mount the exhibition which includes Boltanski’s “Dispersion,” a towering mass of used but still usable clothes in the center of the show’s main gallery. It’s surrounded by serious art presented in an approachable way — bins mounted on plastic milk crates hold much of the work.

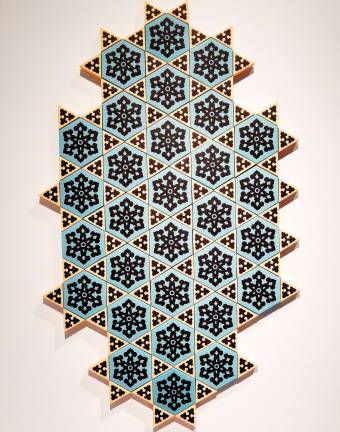

Bright, colorful paper cutouts by Dana Awartani are based on tiles in Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock. The shapes can be used to form a Star of David or patterns like those found in Islamic architecture. Awartani invites visitors to take them, get creative and make something that’s more than the sum of the provided parts. Near them hang racks of Andrea Bowers’ shining satin ribbons painted with texts that she hopes will spark discussion during the current election season. Ribbons have been used to carry slogans and to tie everything from trees to packages to pigtails, but none have borne messages like Bowers’ activist feminist statements. Text artist Lawrence Weiner offers pidgin English stencils and temporary tattoos that pronounce “Now Art Belongs to You and Me.”

Responding to a piece in which Dada star Marcel Duchamp bottled Parisian air a century earlier, Yoko Ono’s “Air Dispensers” come from 25-cent candy machines. Across the gallery, Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ candies wrapped in red, white and blue were the inspiration for the exhibition. Gonzalez-Torres created the piece in 1990 to give artistic voice and form to the idea of impermanence. The candy is sweet but ephemeral, and time and people will change the shape and size of the work. Mutability and decline were personal to the artist; he and his partner both died of AIDS in the ‘90s. Claire Fontaine, an artist collective, fills a windowsill at the close of the show with quarter-sized enameled medallions that read “Please God make tomorrow better.”

Performances will also be given (away) throughout the exhibition, and the museum estimates that, on average, 10,000 of each work will be taken by visitors. The audience is invited to give back by posting photos on the museum’s website, and wall texts with hashtags like #Charity and #LucyLippard, define concepts, identify influential thinkers, and participate in one of the most enduring forms of sharing, the sharing of ideas.

The exhibition runs through Feb. 5 and the art is being reproduced so it won’t run out.