Opponents of a controversial Upper East Side condominium development rallied this week in advance of a key appeal hearing in their fight against the project. Critics claim that the development at 180 East 88th Street, if affirmed by the city, would create a roadmap for other builders to skirt the intent of the city’s zoning resolution.

Construction is in progress on the building in question, a planned 32-story, 523-foot-tall condominium tower near the southwest corner of Third Avenue and East 88th Street. Local land use groups Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts and Carnegie Hill Neighbors, with the support of local elected officials, have appealed the Department of Buildings’ decision to approve of the project. The Board of Standards and Appeals, the agency responsible for reviewing the matter, was scheduled to hold its first hearing on the appeal July 17.

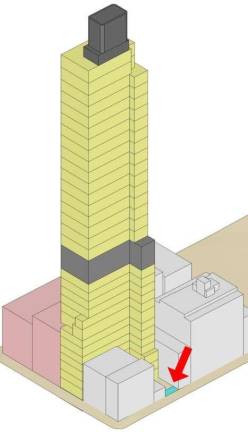

The dispute centers on the building’s L-shaped zoning lot, which fronts on Third Avenue and is set back from East 88th Street by a ten-foot-wide gap. This 10-foot by 22-foot area fronting on East 88th Street, which according to the plans of developer DDG Partners’ will one day be used to access the building’s main entrance, is in fact a separate zoning lot.

This lot, which is too small to build upon, was initially part of the larger lot on which the building is being constructed. The developer later subdivided the original lot to create the tiny new one fronting on East 88th Street and transferred ownership of the carve-out to a different corporate entity also controlled by DDG.

The carve-out’s sole purpose, opponents say, is to allow the developer to build higher and avoid zoning restrictions that would normally apply to buildings fronting on East 88th Street. According to the project’s opponents, the development would be unbuildable in its present form without the carve-out.

“If the Board of Standards and Appeals upholds these tactics, it has the potential to radically alter the character New York’s residential neighborhoods, absent any public input,” Rachel Levy, the executive director of Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts, said at a press conference at City Hall July 16.

Initially, the carve-out was just four feet wide, prompting the DOB stop work on the project in 2016 on the ground that the lot could not be “subdivided into a 4’ lot for the sole purpose of avoiding a zoning lot requirement.” The subdivision was subsequently widened to its current 10-foot depth, after which the DOB lifted the stop work order.

Lo van der Valk, the president of Carnegie Hill Neighbors, said that the project’s approval reinforces the perception, widespread among neighborhood land use groups, that the Department of Buildings is too permissive in its interpretations of the zoning resolution. “We shouldn’t really be here,” he said. “It costs tens of thousands of dollars to fight these developers, and this is really the job of the Department of Buildings.”

In an emailed statement, Department of Buildings spokesperson Andrew Rudansky wrote, “We closely reviewed this project and required the developer to make changes before we issued our final approval. We stand by our decision.”

Ben Kallos, who represents the neighborhood in the City Council, has joined a pending lawsuit against the developer and the city alleging that the developer’s tactics represent “a deliberate attempt to circumvent and nullify” city zoning provisions. Kallos and others said the East 88th Street project speaks to a broader issue of developers finding and exploiting zoning loopholes to build ever-taller towers without regard for neighborhood context. Several speakers at the July 16 press conference referenced the proposed 668-foot condo tower at 200 Amsterdam Avenue on the Upper West Side that is the subject of an ongoing zoning dispute over the project’s irregularly shaped lot.

“It’s kind of like playing a game of whack-a-mole, with an industry that has billions to devote to coming up with new ways to circumvent the rules,” Kallos said, citing tactics such as excessive floor-to-floor ceiling heights, so-called “gerrymandered” zoning lots, and the use of mechanical voids as tools that have been used by developers with increasing frequency in recent years to inflate building heights and property values.

Kallos and other members of the City Council have said that the legislative body needs more resources to expand its land use staff to review projects before they receive approval.

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer said that a ruling in favor of the DDG Partners by the Board of Standards and Appeals’ would signal to other developers that the carve-out tactic is acceptable, opening the door to future tower projects fronting on numbered streets. “Once you set a precedent, then that precedent is always utilized in other instances by developers,” she said.

“These developers should be held to task by the City of New York,” Brewer said. “Their plans do not follow the law.”