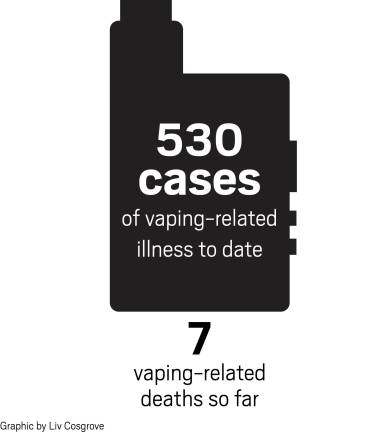

So far, according to the FDA, 530 cases of possible e-cigarette related respiratory illnesses have been reported in 38 states, and a seventh person has died due to vaping-related lung disease. The New York State Department of Health has reported that 10 people in New York City have been sickened with vaping-associated pulmonary illness. So what is going on?

What is vaping?

Vaping is the use of an electronic cigarette, or e-cigarette. The first e-cigarette was developed and patented in 2003 as an aid for smoking cessation. The device arrived in America in 2007. While they may look different, all e-cigarettes have a rechargeable lithium battery, a vaporing chamber and a cartridge that contains a nicotine solution. E-cigarettes deliver nicotine and /or THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol) – the agent in cannabis responsible for many of the psychological effects of marijuana).

What else is in an e-cigarette?

In addition to nicotine and THC, the ingredients in the cartridges can vary widely from brand to brand, and there are now approximately 400 brands. Cartridges can contain water, nicotine, vitamin E acetate, flavorings, polypropylene glycol and/or glycerin. Laboratory studies have also found nitrosamines (a known carcinogen), dimethylene glycol (an ingredient in anti-freeze), formaldehyde, cadmium, lead, and acetone in the cartridge solution. When the ingredient propylene glycol is heated and vaporized, it can form propylene oxide, which is also a known carcinogen.

Originally, the e-cigarette cartridges contained about half the nicotine levels of a pack of traditional cigarettes. Currently, the nicotine levels of the most popular e-cigarette (Juul) have doubled to about the same content of a cigarette pack.

Nicotine, which can be as addicting as alcohol, heroin and codeine, has a broad impact. It can both stimulate and relax the body. People report they feel smarter and more alert, and studies have shown that nicotine enhances attention span and memory. In larger doses, when inhaled deeply, nicotine has a calming effect and reduces feelings of stress. The letdown following these effects makes it harder for vapers to quit.

Moreover, nicotine use leads to "tachyphylaxis," meaning that it takes a greater dose to achieve the same effect. In this way, e-cigarettes have created a new generation of people addicted to nicotine. While national tobacco smoking has fallen to historic lows, there has been a frightening rise in nicotine addiction among teenagers. Between 2011 and 2015, e-cigarette smoking levels rose 900% among high school students.

What happens in the Lungs?

When you vape you inhale an aerosol – a suspension of small liquid particles containing the different products dissolved in the e-cigarette’s cartridge. These ingredients may be transformed by the heating process and become irritating or toxic. As a result, small particles make their way deep into the lungs. Lung x-rays of people who get sick from vaping show shadows similar to those seen with viral or bacterial pneumonias. Unlike those types of pneumonia, vaping pneumonia does not respond to antibiotics or anti-viral medicines.

How is Vaping Different from Smoking?

The hope with vaping was that it would be a true nicotine delivery system and would help smokers gradually wean themselves off cigarettes. (Traditional cigarette smoke contains more than 2,000 chemicals including 146 known carcinogens.) However, the FDA has never approved vaping as a smoking cessation aid. Furthermore, studies show that people using e- cigarettes for smoking cessation have a 10 percent success rate of quitting. By comparison, 26 percent of smokers that use other types of smoking cessation such as nicotine gum or the patch, successfully quit. In addition, other research has shown that up to 52 percent of smokers are now using both electronic and traditional cigarettes at the same time.

FDA Regulation

There is a shocking lack of FDA oversight of e-cigarettes. Despite the fact that they were marketed as a healthier way to smoke and as a way to quit, they were not required to show any evidence of safety or efficacy. In 2008, the FDA announced new regulations that tried to limit the sale of e-cigarettes to minors. However, since more than 50 percent of e-cigarettes are bought online, and there is a considerable black market, the current FDA regulations are inadequate.

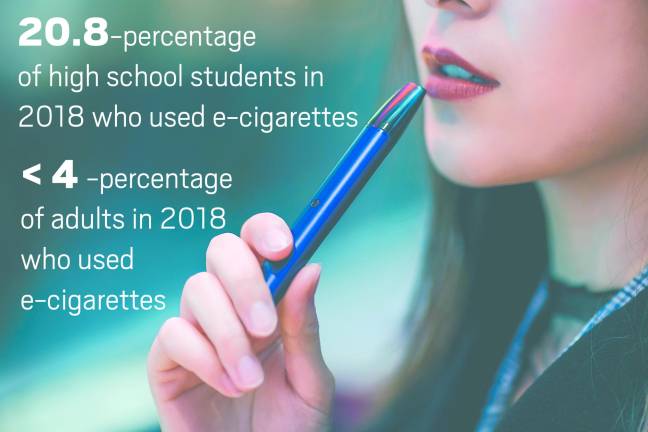

In the U.S., teens are more likely to use e-cigarettes than adults are. In 2018, 4.9 percent of middle school students and 20.8 percent of high school students used e-cigarettes. By comparison, less than 4 percent of adults use e-cigarettes.

Symptoms of Respiratory Illness

The disease as it has been reported frequently begins with a dry cough and pleuritic chest pain (sharp pain with deep breaths). These early symptoms begin several days or weeks before the person requires hospitalization. A fast heart rate, fever, chills and fatigue are also reported, as are GI symptoms, which may appear before the respiratory symptoms. These may include vomiting, abdominal symptoms and diarrhea.

By the time the person is sick enough to require hospitalization, findings of low oxygen in the blood leading to respiratory failure may occur. This is usually treated by giving oxygen or in extreme cases using intubation with mechanical ventilators.

The symptoms may be confused with pneumonia but these patients do not respond to antibiotics and the commonality is that they used e-cigarettes with THC, and/or nicotine plus THC. No specific agent(s) has been consistently associated with this illness. In some cases, washings from the airway using a bronchoscope as well as biopsies of the lung have shown fatty products in white blood cells. This finding is associated with “lipoid pneumonia,” a non-infectious pneumonia resulting from the inhalation of oils such as those that may be used in vaping solutions.

There is no specific treatment, but systemic steroids seemed to speed recovery.

Final Thoughts

What we may be seeing is the tip of the iceberg, with many other individuals developing less severe forms of the disease. Even as we search for effective responses and treatments for these short-term effects, we need to keep in mind the potential for long-term effects. In the case of cigarettes, we know that lung cancers and other chronic related diseases may only become apparent long after an individual stops smoking. There is very real concern that the cases now being reported are just the start of new long-term public health problems.

E. Neil Schachter, MD, is the Maurice Hexter Professor of (Pulmonary) Medicine and a Professor of Environmental Medicine and Public Health at The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the Medical Director of Pulmonary Rehabilitation at Mount Sinai Hospital