Art Under the Open Sky

MoMA continues its Virtual Views series with an online show devoted to its renowned Sculpture Garden

It’s the unofficial start of summer, and as New York City prepares to reopen, the itch to get outside and commune with nature becomes stronger and stronger. Irresistible, in fact. The city’s numerous parks and green spaces are a welcome refuge from the confines of the Manhattan apartment, to be sure. The beaches, too. But when the day is done and you find yourself with nowhere to go but home and back to your laptop, why not continue the dream of sunny meanderings in the open air and go to MoMA’s website for curated views and conversation about the Museum’s famed Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden?

Pretty much every art-loving New Yorker and millions of tourists have visited this jewel in the heart of Midtown, if only to take a time-out from the art inside the galleries, contemplate the Chinese elms or plop down in a chair alongside one of the rectangular pools. It’s been a popular date spot, summer music destination and the location for a scene in John Cassavetes’s directorial film debut, “Shadows” (1959).

But how much do you really know about the garden — the design, the sculptures, the plantings, the parties, the protests, the music and the birds in the trees? No worries. MoMA’s weekly series, Virtual Views, will bring you up to speed and make you yearn for the museum’s re-opening and wish you had not taken this walled art park, with its soothing vibe, for granted.

As someone who lived on West 53rd Street in the 1980s and worked for years in the former Time-Life Building nearby, I developed the habit of heading to the Sculpture Garden on my lunch hour for Zen contemplation and relaxation, sometimes after-hours if the museum was open. MoMA’s virtual offerings — audio, video, photos, guided meditation and bird watching tips — make me nostalgic for the garden then and the garden now.

"An Outdoor Gallery"

This year marks the 81st anniversary of the fabled green space, where Yayoi Kusama staged a naked happening in 1969, “Grand Orgy to Awaken the Dead,” to protest the Museum’s penchant for “dead” art at the expense of more vital, contemporary work.

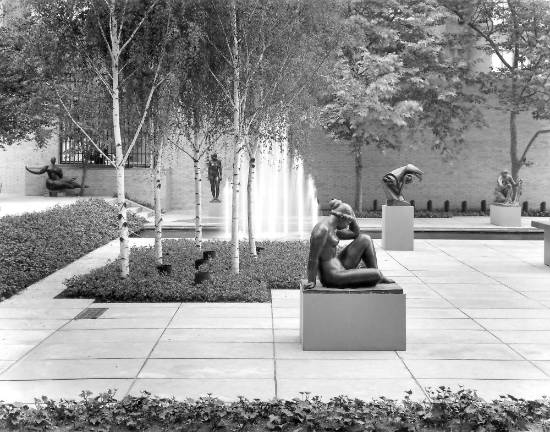

The garden first opened in 1939, on the site of two townhouses that had belonged to the Rockefeller family, and has been re-imagined several times since, the first time by Philip Johnson in 1953, the most recent by Yoshio Taniguchi in 2004.

As Ann Temkin, curator in charge of the Sculpture Garden, states in a video Q&A with Peter Reed, senior deputy director: “The 1953 garden is pretty much the model for what we see today ... with the marble paving stones, the very arranged rooms that are divided by clumps of plantings and trees and two long pools, a wall along the north edge. All of these things were originally Johnson’s vision.”

She adds: “Johnson also called it an outdoor gallery ... It was really a room for art that just happened to be under the open sky.”

Importantly, he wanted to bring the feel of an Italian piazza to New York City — to create a place for sculpture but a social space, too, Reed says.

As the site evolved, the collection grew in tandem with the landscape and art trends. For the last half-century, the focus has been mainly on abstract pieces by the likes of Alexander Calder, Ellsworth Kelly, Donald Judd, Louise Nevelson and Tony Smith.

Staying Relevant

But there’s also been a concerted effort in the last 15 years to bring the outdoor gallery into the 21st century and exhibit figural sculptures by contemporary artists. Think Katharina Fritsch (“Group of Figures,” 2006-08), Pierre Huyghe (“Untilled [Reclining Female Nude],” 2012, a nude figure with her head encased in a beehive), and Peter Fischli and David Weiss (“Snowman,” 1987/2016, a real snowman that stayed chill in a glass-doored freezer).

Indeed, in the interests of staying relevant, new works are rotated in every spring, with towering cranes lifting multi-ton pieces into place from the garden’s northern end on West 54th Street. (The COVID-19 crisis has put those plans on hold this year.)

A constant of the collection — a 60-year veteran — is Picasso’s “She-Goat” (1950; cast 1952). Alfred Barr, MoMA’s first director, was hell-bent on acquiring the bronze goat, so much so that he devoted nearly 10 years to the effort. It entered the collection in 1959.

The pregnant nanny is a veritable crazy quilt of random finds that Picasso used to assemble the creature — a palm frond for the back, a wicker basket for the belly and two ceramic jugs for the udder. The pieces were held together by plaster.

Says Temkin: “You can tell that she is a favorite because if you were to look at her head-on, you would see that the patina on her snout is completely rubbed off by affectionate petting.”

Now, take a mental health break and click on the meditation sequence on MoMA’s website. Get a comfortable seat and imagine yourself in the green oasis. Let Security Supervisor Chet Gold be your guide: “What you will be doing is breathing to the counts — I’m gonna go in two, three [inhale], out two, three [exhale]. So breathe with me and focus on the counts.”

Just breathe.