For decades, the name “Nina” conjured thoughts of hidden squiggles, swirls, and surprises, as thousands of fans hunted for the NINAs hidden by the master caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, who buried his daughter’s name as he took his magic pen to immortalize every major Broadway opening in The New York Times.

The NINAs were “a boon to science,” too, according to Ellen Stern, who took five years and conducted 325 interviews for her biography, “Hirschfeld.” The Federal Aviation Agency wanted “to use the drawings to test perceptual ability.” The Department of Defense apparently wanted to use NINAs “to model the effects of camouflage on target search and detection.”

According to Stern, the real Nina seems to have transformed from a happy youngster to a miserable adult — dropping out of schools, disposing of careers like discarded tissues and, saddest of all, having a fractious relationship with her famous father. Stern writes: “For such an observer, Hirschfeld is remarkably naïve about mental distress.”

Stern outlines it all for us in her breezy narrative. Just when you’re beginning to doubt how she could possibly know who said what on such-and-such a date, you’ll remember she’s provided an extensive section of explanatory notes.

Hirschfeld’s drawings appeared widely, from movie posters to TV Guide and The New Yorker. In the full index, you’ll find Julie Andrews to Flo Ziegfeld and everyone in between, including Josephine Baker, George Balanchine, and Tommy Tune, a-listers like Jacqueline Kennedy and politicos like Lyndon Baines Johnson.

Many-Years Feud

Now we come to the elephant — or Hirschfeld — not in the room: How is it that “Hirschfeld” has only one illustrative drawing?

When I Zoom with Stern from her vacation rental on Cape Cod, the Upper West Sider expands. Margo Feiden, the subject of multiple pages in Stern’s book, represented Hirschfeld’s work exclusively for many years. She apparently thought her rights would continue after his 2003 death, just short of his 100th birthday. A many-years feud between Feiden and The Hirschfeld Foundation was finally settled in October 2020. The United States District Court, Southern District of New York, found for The Foundation, granting it complete control of all of Al Hirschfeld’s work. The decision came too late for Stern’s book.

So if you want to see how Hirschfeld immortalized “My Fair Lady” or “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” and if you yearn to feast on the caricatures, you’ll have to watch the 1997 documentary, “The Line King.” Or Google The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. “Hirschfeld” is about the man’s life.

Ellen Stern wrote the “Best Bets” column in New York Magazine for ten years. She was an editor at the New York Daily News and a senior writer at GQ Magazine. She first met Hirschfeld when she interviewed him for GQ in 1987. He inscribed his book, “Show Business Is No Business,” this way: “For Ellen Stern, my biographer.” The seed was there, and sprouted “in 2011, when his widow sold the [East 95th Street] town house where he’d lived, worked, and hosted so many starry soirées.”

Pure Joy

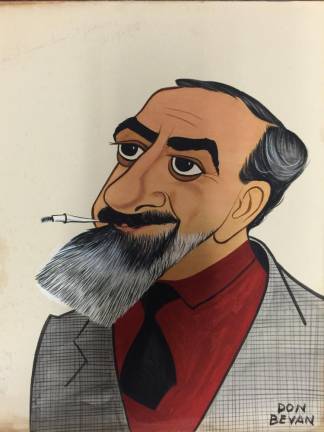

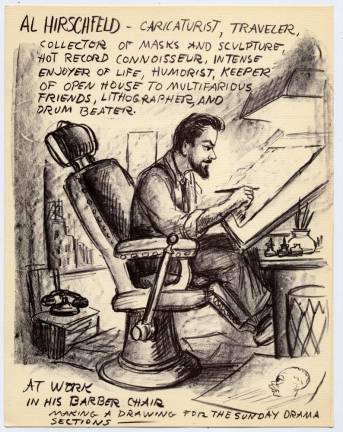

“Hirschfeld” gallops in present tense. Stern revels in the travel, gossip, and tales of legendary dinner parties. She begins in the caricaturist’s studio, where he draws every day in his “slippered tootsies,” seated in his beloved barber chair, and creating “several drawings a week, several hundred a year, ten thousand in a lifetime.” His distinctive line drawings are unmistakable: swirls, swoops, pure joy. It’s an immediate portrait of the artist who captured “the essence of Merman, Mostel, or Bernstein ... [for] The New York Times, the Herald Tribune, TV Guide, Vanity Fair,” and more.

After a swift intro, it’s Hirschfeld’s beginnings in a Jewish neighborhood of St. Louis, through an eventful life that took him to Paris, Israel, Japan, and to New York, where he got to know everyone in the theater world. Over time, he set up studios in various Manhattan neighborhoods, at one point perched on the roof of the famous Osborne apartment building on West 57th Street.

Thrice married, Hirschfeld’s calendar was always full. There were the days in the studio, of course, but every night there was theater or dinner parties or soirées to host.

Stern’s narrative includes some surprises: Though Hirschfeld drawings graced The Times’ theater coverage beginning in 1928 and continued on-and-off for over 75 years, he was a freelancer, with no guarantee of work. He was axed in 1990, then reinstated, with his first contract at the tender age of 87. Yet when Carol Channing’s death was front page news, it was accompanied by Hirschfeld’s iconic drawing. Google Channing’s obit now and you’ll see the definitive 1964 “Hello, Dolly!”

Home for Stern is a classic six on West End Avenue. A widow with two grown children, she immersed herself in Hirschfeld-land, talking with actors, playwrights, poker buddies, friends and neighbors. When she’d interviewed Hirschfeld, she found him “charming and real.” Many who visit the Al Hirschfeld Theater on West 45th Street may know nothing of the great caricaturist who “had a circle of friends who worshipped him.” Stern’s biography would be a good introduction.