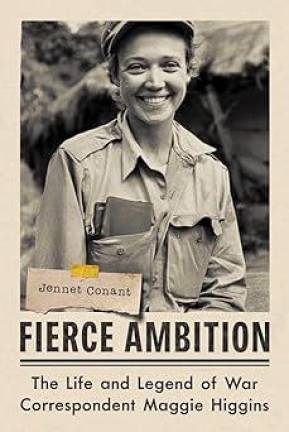

Legendary War Correspondent Maggie Higgins Chronicled by Conant

From the tail end of World War II and through the Korean and early days of the Vietnam Wars, she was one of the eras most famous war correspondents, an exclusive club that had few women. Jennet Conant chronicles Higgin’s trailblazing life in a new bio, “Fierce Ambition: The Life and Legend of War Correspondent Maggie Higgins.

Talk about good timing, for sad reasons. We have all been watching troubling news from international hot spots, often admiring the war time correspondents, wearing flak jackets and helmets while incoming rockets explode in the background on live broadcasts. Nobody is surprised in the current Israel-Hamas War or the war in Ukraine that women are reporting the dangerous and sometimes terrifying events along with their male colleagues at the vanguard. But it was not always so.

Which is why “Fierce Ambition: The Life and Legend of War Correspondent Maggie Higgins,” the latest book by UES historian/journalist Jennet Conant is so important. Released at the end of October, the book tells the story of one Marguerite—known as Maggie—Higgins, who attended UC Berkeley and then Columbia Graduate School of Journalism and at 20, became a cub reporter for the New York Herald Tribune. She always had one dream: to be a foreign correspondent. She became a legend in her own time.

“I was drawn to the story of Marguerite Higgins because she is not a conventional heroine,” Conant told me. “She is a complicated, problematic character—as interesting for her virtues as her vices. She should be much better known, but she didn’t fit neatly into the feminist narrative of who qualifies as a role model. She was too pretty, too provocative, too ambitious, too badly behaved, and slept with way too many men on her relentless climb to the top. Just too, too much for the old feminist canon.”

“She wasn’t a feminist, per se,” Conant said in a recent interview with NPR. “She just wanted equal opportunity for herself, not for her sex. And so she broke down the doors because of her unbridled ambition.”

Higgins became one of the most famous war correspondents in the world from 1945 to 1965. She was barred from front line combat reporting in World War II but managed to be one of the first to get into Buchenwald and the Dachau concentrations camps when they were liberated in the waning days of WWII when she was only 24 years old.

In the Korean War, she was with the United States Marines at Inchon, a brutal four day siege that marked a major turning point of that war for the United Nations forces. She was the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for international reporting–for her frontline dispatches during the Korean War. No other woman would win a Pulitzer in that category for 30 years. She died in Washington D.C. at the age of 45 after contracting Leishmania, a painful parasitic infection she contracted while reporting in Vietnam. She is buried in Arlington Cemetery since she had married a military man, Air Force Lt. General William Hall.

“She was also infamous for being willing to do almost anything for a scoop,” says her biographer. “Her looks—fetchingly blonde and beautiful—and leggy model figure, inevitably gave rise to complaints that she was trading on her sex—and trading sexual favors for information. But Maggie always shrugged off the criticism as merely an expression of male envy.”

“Fierce Ambition” makes clear that male reporters bitterly resented Higgins, and openly accused her of using her feminine wiles to gain unfair advantage: for example, to get a lift to the front lines, an exclusive interview with a general, and access to classified military information. But as Conant says, “perhaps we owe a debt to the difficult women of the past: those who raised their voices, caused a ruckus, challenged authority, and were occasionally badly behaved in order to get things done in traditionally male-dominated professions. I think many of the labels and insults attached to unruly women— ambitious, aggressive, manipulative, seductive, etc.—were just a way to diminish them, and keep them in their place.”

Higgins faced other controversies–including a bitter feud with David Halberstam who was a sharp critic of America in Vietnam and eventually questioned her own opinions–during the Vietnam War. She wrote “Our Vietnam Nighmare” which was published a year before she died.

She broke the rules at a time when women were expected to stay home or, if reporting, stick to the soft stuff. Higgins decidedly did not.

Conant is married to a pretty good reporter himself, Steve Kroft of “60 Minutes” fame. He says, “if anything has dissuaded me from writing a book of my own, its having watched and lived through my wife writing seven of them: The struggle to come up with a great idea, a year of research, then filling hundreds of pages. This is her best yet. I’m very proud of her.”

The suspicions and jealousy Maggie Higgins faced was simply a sign of those times. “It reminds me of something Nora Ephron once said,” says Conant, “about how she could not imagine why any woman would want to be a pioneer because of all the abuse she would have to take.” (Interestingly, Ephron spent the last two decades of her life trying to get a movie made about Higgins’ escapades in Korea.)

This book is catching a moment for sure. Jennet Conant is the perfect biographer for Maggie Higgins,” notes historian Evan Thomas. “She knows the world of journalism and has a keen and discerning eye for quirks of character.” Conant has strong genes: her grandfather served as President of Harvard, and worked closely with Robert Oppenheimer on the Manhattan Project.

As we dare to watch the news these days, we hardly blink when seeing women like Christiane Amanpour, Clarissa Ward or Ellison Barber avoiding the missiles and interviewing people caught up in war. “I don’t think Maggie Higgins has an equivalent today, because she knocked down so many obstacles in her path,” says Conant. “But she opened the way for the female reporters who came behind her.”

“I don’t think Maggie Higgins has an equivalent today, because she knocked down so many obstacles in her path. But she opened the way for the female reporters who came behind her.” Jenet Conant