“Slick” Barkley Hendricks is First Artist of Color to Get Frick Exhibit

Frick Madison hosts its first solo show of works by an artist of color through Jan. 7th at the museum’s “temporary” home while its permanent home completes a major renovation. Come March 3 the Frick Madison, will close down entirely after a 2 1/2 year run, but the newly renovated Frick Collection won’t open until late 2024.

Step off the elevator on the fourth floor of Frick Madison and witness perhaps the most shocking–but in a good way–juxtaposition in the museum’s 88-year history: “Lawdy Mama” a gold-leaf icon of a Black woman with a puffy Afro painted in 1969 is framed by two 18th century sculptures by Jean-Antoine Houdon.

Turn the corner and behold a fussy Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds’ “Lady Skipwith” in tulle before encountering two rooms filled with paintings unlike anything seen before at this venerable institution: more than a dozen portraits of contemporary Black figures by Philadelphia-born Barkley Hendricks (1945-2017), a painter who revered the Old Masters and considered the Frick one of his favorite museums.

A professor of art at Connecticut College for nearly four decades, with a studio in New London, he went on a portrait spree in the late 1960s that lasted until the early 1980s, drawing inspiration from European masters like Rembrandt, Bronzino and Moroni—but also nodding to 20th century Abstraction and Minimalism—to create his own distinct oeuvre.

As he once commented, “I wasn’t a part of any ‘school’. The association I had with artists in Philadelphia didn’t inspire me in any direction other than my own. I spent my time looking to the Old Masters.”

The mostly full-length portraits loom large and demand your attention. They are hyper realistic, with an emphasis on hip clothing and accessories. There’s great attention paid to detail—reflections in eyeglasses, the texture of faded denim, the shimmering of metal jewelry. The works are a salute to “cool,” representations of Black figures that depart from images of struggle and subservience and, in the words of co-curator Antwaun Sargent, highlight the overlooked “beauty, grandeur, and style of Black people.”

As Hendricks said about the visual culture of the late sixties and seventies, according to the exhibit catalog: “How many black people...were part of any kind of visual information that didn’t deal with what I call the misery of my peeps? You know you can always find visual information that deals with the hardship, slavery, and all the rest of it...I’m trying to sort of address a situation that’s not part of that.”

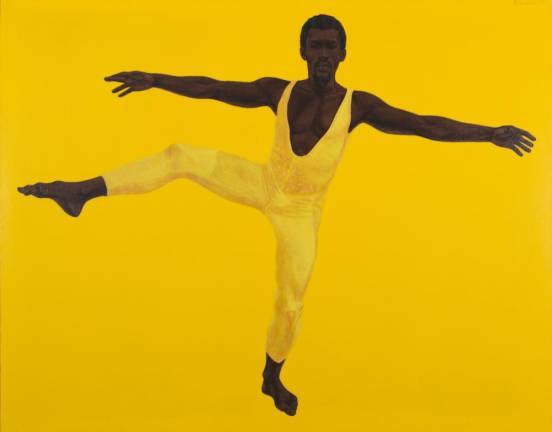

Indeed, the show boasts a remarkable collection of dressed up “sistas” and dudes strutting their stuff. The subjects are bold and wear boldly colored garments like the saffron-yellow leotard in “Woody,” painted in 1973. They are proud, and they are cheeky to boot.

There’s a lot of humor and posturing here. Hendricks painted from life, but he also used a camera to capture his subjects, mostly family and friends, but also strangers he bumped into on the street that he liked the looks of and asked to pose. He called his camera his “mechanical sketchbook” and used photos in lieu of preparatory drawings to paint from.

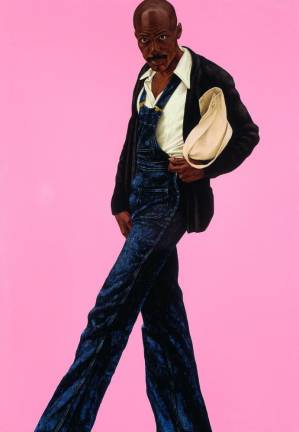

“Misc. Tyrone (Tyrone Smith)” painted in 1976 is but one example of the artist’s random encounter with a stranger—in this case, on the streets of Philly—that resulted in a glowing portrait. Call it “Portrait of a Man in Overalls.” Smith was more than happy to have his photo taken in the middle of downtown Philly, where a crowd gathered to watch the theatrics as he “was going through his moves,” Hendricks later recounted of the spur-of-the-moment photo session.

Per the Frick’s website, “Hendricks set Smith’s angular pose against a vibrant pink background, inspired perhaps by his sense of his subject’s personality.”

The pictures’ monochromatic backgrounds—Barbie pink, in the case of Smith’s portrait—owe a debt to color field painting. The details of settings, like apartments or city streets, are stripped away, and the subjects appear in isolation on flat, solid-color fields, which lend them real presence, power and agency.

Hendricks painted his models in oil and then applied varnish, but he used matte acrylic paint for the backgrounds. As co-curator Aimee Ng writes in a catalog essay about the use of different media–a technique employed by Leonardo da Vinci in the 15th century–“The varnished oil-painted figures glisten in light, as if on a separate plane from the matte acrylic.” They practically float.

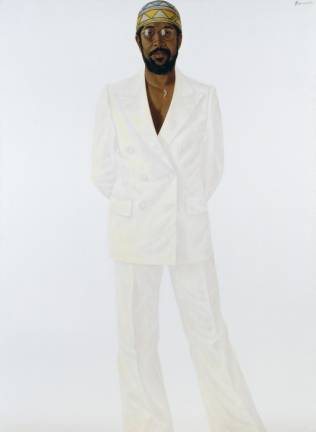

A side room showcases Hendricks’ “limited palette” white-on-white works—gleaming oil-painted and varnished figures dressed in white, set against matte-white backgrounds that dramatically accentuate Black skin tones.

About “Slick” a 1977 a self-portrait, the artist said: “My sister said to me one day, ‘You think you’re so slick, just wait, one day a woman is going to straighten you out.’ Ah, a great title for a painting.”

And fans of the Frick and Barkley Hendricks may have an even more urgent reason to visit this exhibit at Frick Madison in its final weeks. The acclaimed temporary home of The Frick Collection will close its doors on March 3, 2024, as the institution begins preparing for its move back to its historic home at 1 East 70th Street, which is now nearing the completion of a significant renovation and enhancement project. It will reopen in late 2024.

Commented Ian Wardropper, the Frick’s Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Director of the pending move from Frick Madison: “We will savor our remaining weeks in the Breuer building, which has provided such a unique setting for our permanent collection during the past two and a half years. This remarkable space has provided up-close viewing opportunities for our reframed collections. We have enjoyed presenting the Frick’s iconic Vermeers, Rembrandts, and other Old Masters—as well as sculptures, porcelains, rugs, bronzes, and decorative arts objects—grouped in ways not possible in the historic mansion.

He continued, “It has been extremely gratifying to have our efforts at Frick Madison praised by Frick devotees and critics alike, which in turn has helped us to reach new audiences unfamiliar with the institution’s masterworks. During the next three months, we look forward to welcoming both new and returning visitors to be inspired one final time by Frick Madison, before closing the doors of this once-in-a-lifetime installation.”