Turning Found Parts into Art

Morningside Heights artist is given his building as a canvas

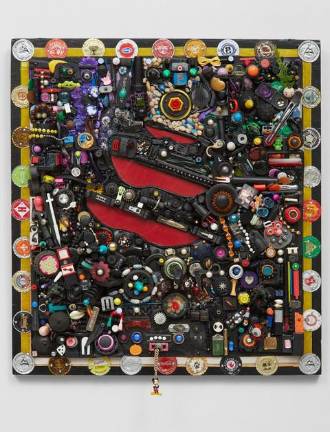

The adage that someone’s trash can become another’s treasure is reinforced daily at the home of Mark Gordon. The retired lighting designer and electrical contractor has made a second career out of creating art from found objects. From Scrabble tiles to bottle caps to crack vial tops, all of the materials he uses he’s collected on the city’s streets.

When the over 100-year-old elevators of his building at 420 Riverside Drive were being replaced, tenants expressed sadness at the loss of these pieces of history, which were decorated with ornate copper-clad brass paneling. Gordon offered his solution; he would preserve their parts by transforming them into works of art.

This labor of love took over one year, and included countless hours of removing the layers of paint, dust and grime that accumulated since the elevators had been installed in 1912. It resulted in 16 unique pieces of “elevated art,” all of which are displayed in the building for residents to enjoy.

A beloved resident of the building since 1983, Gordon had done much of its rewiring and repairing, so was given free rein to construct “the elevator project,” as he refers to it. “I was given carte blanche to treat the building as my canvas,” he explained. “It was perfect for me.”

You find objects every day. Which have been the most unusual?

I don’t go out looking for things; I just find things. Last week, for instance, I found a chromed truck tire rim, which I brought home. Is it unusual, no? There are things, however, that interest me, shape-wise. When I first started making these things, I called what I did, “bulbus,” because I seemed to have been very interested in the bulb, rounded shapes, and was using lights. Originally, that was what attracted to me to various things, a bulbus shape to which I might add Lord knows what else.

Some of your work includes crack vial tops, which you would gather in Morningside Park.

I moved to the Morningside Heights area in 1983. At night, my wife was not the only woman who would walk home down the middle of the street because it could be dangerous for a young lady alone on the sidewalk. I discovered Morningside Park in about 1987. I had a job remodeling a brownstone on Manhattan Avenue, down in Harlem. It was a complete dump at that time. It’s all staircases and they were all falling apart. It was completely overgrown and it was filled with crack vials. I would gather them up like I was going to pick nuts. When the epidemic hit, that park was especially filled with debris of drug addicts. They didn’t clean this up until 2010, something like that. It’s in excellent shape now.

Take us through the process of putting together the first piece of the elevator project.

One of the pieces is from the old manual controls for the elevator, which is the switch that you turn left and right to go up or down. And then the center is the stop. It was the control for the elevator car and I thought it was really cool and that it deserved its own place in the universe. That is a true found object that’s almost 95 percent what it is. There’s just a couple of things added to it. Stripping, de-greasing, using wire brushes, sanders, grinders, cleaning, you name it. It was in there for 100 years, you know. There was serious dirt and oil and more dirt. It was like cleaning off parts of a car.

What feedback did you get from residents?

I put up the first series, which was the five bottom panels, which were in public areas. Two of them went up at the roof accesses; three of them were downstairs where the freight elevator is in the lobby. So I put those five in and people were really pleased with that. And then I did the next series, which was stuff mostly from the passenger elevators, and those three went in the stairwell between the twelfth floor and the roof. It was a huge stairwell with absolutely nothing there. People saw that and thought it was really great because it really makes the space as you go upstairs. And then the other six were put out to bid, so to speak, because as I was putting up the ones downstairs, somebody said, in an Italian accent, “I want one of these on my floor.” And I said, “Well, ask the board. Every person on your floor has to say yes.” So the ninth floor did it and then the tenth floor, and then other floors asked for them. And since I was putting these together in the building shop, the guys wanted one for their employees’ lounge.

Tell us a little bit about the building’s history and why it’s so special to you.

It was a mansion and it was torn down and this building was erected in 1912. This was a high-end apartment building when it first opened. It went co-op in 1985. In the first five years after that, a lot of people left and a certain number of people moved in, all of whom had or were having kids, including myself and my wife. There were a lot of people in the building who raised their kids together and who felt a certain sense of community with each other that has lasted a long time. And it’s finally changing because we have 84 apartments and if three or four apartments every year changes hands, that means over a ten-year period, half the building is different. So the past cannot be recreated, but a lot of us really feel that we have a special building.

To see more of Mark Gordon's work: markgordonsculptures.com