I liked the way he played and sang. And I liked the things he said when he sang ... I was like a Woody Guthrie jukebox. I was completely taken over by him, by his spirit. He had so much to give! He was like a link in a chain for me. You could listen to his songs and actually learn how to live.

– Bob Dylan

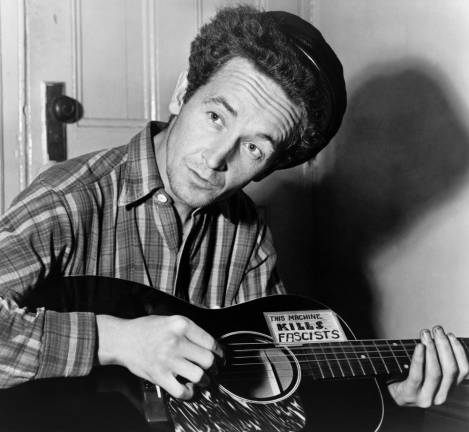

Woody Guthrie, the Dust Bowl poet who spoke to legions of forgotten Americans and inspired such folk-music legends as Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger, still has a place in New York City’s heart. In 1967, Guthrie died of Huntington’s disease after remaining in a hospital in Morristown, N.J.

Beginning Feb. 18 and running through May 22, the Morgan Library & Museum will open an exhibit intended to “tell the story of Woody Guthrie, the great American troubadour and writer.”

Guthrie, who was born in 1912 in rural Oklahoma, had an impact on the American psyche that was acutely felt around the time of the Great Depression in the United States. The display is entitled “Woody Guthrie: People Are the Song.”

3,000 Folk Songs

As the Morgan literature notes, Guthrie wrote an astounding three thousand folk songs, and the institution calls “This Land Is Your Land” “the world’s most famous protest song.”

The Morgan adds: “But he was not only a songwriter, and his subject matter extended well beyond labor politics. The full corpus of his creativity — including lyrics, poetry, artwork, and largely unpublished prose writings — encompassed topics such as the environment, love, sex, spirituality, family, and racial justice. Guthrie created a personal philosophy that has impacted generations of Americans and inspired musician-activists from Pete Seeger and Bruce Springsteen to Ani DiFranco and Chuck D.”

No doubt Woody also blazed a path for his son, the singer and songwriter Arlo Guthrie, best known for his own classic, “Alice’s Restaurant.”

“The Morgan’s upcoming exhibition tells the story of this great American troubadour and writer through an extraordinary selection of instruments, manuscripts, objects, photographs, books, art, and audiovisual media, assembled from the preeminent Guthrie holdings of the Woody Guthrie Center and the private collection of Barry and Judy Ollman,” the Morgan points out. “Prominent among these rarely seen objects are the original, handwritten song lyrics to ‘This Land Is Your Land,’ which Guthrie composed just a few blocks away from the Morgan in 1940, maintain a vital relevance in today’s world.”

Legendary Life

Guthrie’s life is the stuff of legends.

Dylan knew all along. He trekked from his home state of Minnesota partly in the hope of meeting Guthrie, then confined to a hospital in Morristown, N.J., in January 1961. Dylan visited Guthrie there on many occasions.

When it came time for Dylan to record songs for his first album for Columbia Records later in 1961, he included his homage, “Song to Woody.”

Guthrie was born in a small town in Oklahoma in 1912. He wrote about his journeys in a memoir called “Bound for Glory,” which served as the title for an Oscar-nominated biopic of the same name in 1976, starring Keith Carradine in the title role.

Dylan remained an ardent Guthrie acolyte. He recited an original poem, which he entitled “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie,” during a show in New York in 1963.

And a few months after Guthrie died, on October 3, 1967, Dylan came out of a self-imposed exile to make his first stage appearance in 20 months, during a tribute concert on Jan. 20, 1968. If you have never heard the three-song set delivered that evening by Dylan and The Band – “I Ain’t Got No Home,” (especially the riveting) “Dear Mrs. Roosevelt” and a rocking “Grand Coulee Dam” – do yourself a favor and RUN to YouTube and check it out.

Guthrie, a great contrarian, would surely have smiled at Dylan’s ironic selection of the patriotic “Grand Coulee Dam,” performed during the time of the clamorous anti-Vietnam War protests, containing the words, “always the flying fortress, that flies for Uncle Sam.”

Speaking of the latter song, I have a personal footnote to the Guthrie saga. A few years ago, I was visiting a friend in Seattle, and she and I decided to go on a road trip. But where? North to Vancouver? South to Portland?

We set out east to visit the Grand Coulee Dam. It was a fun bit of tourist Americana. At one point, during our tour of the site, David, a Washington State University student who served as our guide, asked the group excitedly, “I bet nobody can name the person who inspired the statue of the man playing the guitar.”

Needless to say, one person there could! David was impressed to learn that Woody Guthrie was so well known.

Well, we could build a statue in every state in the land, and it would not do Woody Guthrie justice.

“There was an innocence to Woody Guthrie,” Dylan said. “I know that’s what I was looking for – like a lost innocence – cos after him, it’s over. It’s over.”

Bob Dylan was an ardent Guthrie acolyte. He recited an original poem, which he entitled “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie,” during a show in New York in 1963.