A Walking Tour of Historic East 69th Street

A deep dive of a block’s past engenders advocacy for neighborhood preservation

Residents of leafy East 69th Street spanning First and Second Avenues were treated to a deep dive of their block’s history during a walking tour on Sunday, October 16, 2022. The tour was conducted by architectural historians and preservationists James Russiello and Marianne R. Hurley of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

This scenic stretch of East 69th Street is nestled within the Lenox Hill neighborhood, and was once part of a large estate, since 1797, of John Jones, a member of one of the many Knickerbocker establishment families that purchased farming lands along the river as country retreats. (The phrase “Keeping up with the Joneses” originates with this clan.) Later known as Jones’ Wood, the largest parcel was eventually developed in the early 20th century into what became Rockefeller University.

Houses numbered 310 to 332 East 69th Street on the block’s south side exist within a remarkably intact row of Neo-Grec style brownstones built between 1879-1880 and characterized by two-story Dutch style stoops. The rowhouses numbered 322 to 344 and the Hungarian Church at 346 East 69th Street compose The East 69th Street Historic District of the National Register of Historic Places.

Old Law tenements built in the 1880s lined the north side of the block, three of which remain, altered, at 309 and 321 East 69th Street. They were replaced in the early 1960s by the three white-bricked multi-unit apartment buildings at 315, 333 and 345 East 69th Street.

Initially, they were rentals designed to attract the post-war urban population who did not flee to the cookie-cutter suburbs, such as childless couples, singles and professional women. They went co-op in the 1980s. They were inspired by the success of the now landmarked Manhattan House at 200 East 66th Street — the first white brick multifamily building on the Upper East Side, built between 1947-1951, and designed by Mayer & Whittlesey, with Skidmore, Owings and Merrill as associate architects.

Rare Ecclesiastical Work

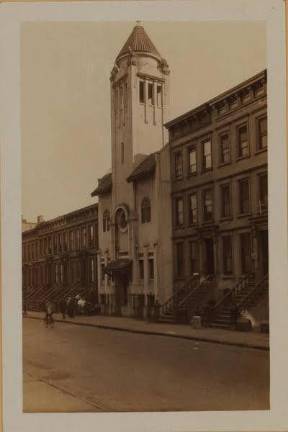

The highlight of the tour was a visit inside The First Hungarian Reformed Church of New York City, situated midblock on the site of two former rowhouses, with an adjacent pastorage. An early and rare ecclesiastical work designed by the Hungarian-born architect Emery Roth, built in 1915, it was designated as a NYC Individual Landmark in 2019.

The symmetrical church facade features the official shields of the U.S. and Hungary on either side of an 80-foot tower which houses, and regularly rings, the bell brought from its original Lower East Side location where the congregation was formed in 1895, following the Hungarian migration uptown. (East 79th Street and Second Avenue was once known as the heart of “Little Hungary.”)

Inside the church, Hurley, who wrote the landmark designation report of the church, and the church’s own Lehel Frank Deak showed off the sanctuary’s pulpit, carved from a single piece of white marble. Istvan Balla, who has worked with the church for 67 years, noted that the elaborate coffered ceiling originated in a pavilion for the 1939 World’s Fair.

Three bronze panels in the lobby depicting the life of Hungarian patriot Lajos Kossuth that were briefly installed on his Riverside Drive monument, were gifted to the church in 1930 by sculptor Janos Horvai. The church remains in use by its original Reformed congregation, who live throughout the greater metropolitan region and travel there to attend Sunday services and an afternoon of fellowship. A Baptist and a Korean congregation use the church for their own Sunday services.

Some of the many notable past residents recalled by tourgoers include NBC newscaster Chet Huntley 1911–1974), critic Harold Clurman 1901–1980), fashion designer Geoffrey Beene (1924–2004), producer Richard Lewine (1910–2005), and architect Der Scutt (1934–2010).

The block’s many London plane and other trees, seasonal floral tree pits, and other embellishments are maintained by the East 69th Street Association. Formed in 1962, it successfully fought off rezoning in 1964 that would have permitted commercial development within the block.

Form of Activism

The idea to stage a customized history walk of East 69th Street was prompted by a tour that Russiello led this past spring for the Municipal Art Society of the Czech areas of the Yorkville neighborhood, starting at 72nd Street.

With development coming to my Upper East Side neighborhood (the latest example being the 200+ foot NY Blood Center tower which successfully sought a mid-block zoning variance), it struck me that, in addition to having fun and fostering community, a walking tour presents the opportunity to engender greater appreciation for NYC’s unique architecture; and once that happens, they might be more likely to engage in neighborhood beautification and preservation.

Will more New Yorkers be taking – even conducting — tours of their own blocks soon? I hope that future walks will be organized by my own and other block associations, even individuals. A great model can be found in the Municipal Art Society’s Jane’s Walks. An annual event celebrating Jane Jacobs, who successfully fought Robert Moses’ proposal to extend Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park in the 1950s, it provides ordinary New Yorkers with an opportunity and training to give a tour of their own blocks, neighborhood, or other historic site.

Says Russiello: “New York is an infinitely walkable city, and there’s a story around every corner. The best part of the tours are connecting with people and learning what parts of the city that they value and want preserved.”

Jacquelyn Ottman has resided on East 69th Street since 1980, and is a past president of the East 69th Street Association. A fifth generation member of a New York family of meat purveyors to city restaurants, she is the author of “Ottman & Company: Meatpacking District Pioneers.” She regularly conducts walking tours of the historic meatpacking district, and gives online talks and in-person book signings.