Erik Bottcher Aims to Address Mental Health Citywide

In his early days as Council Member, Bottcher gets personal

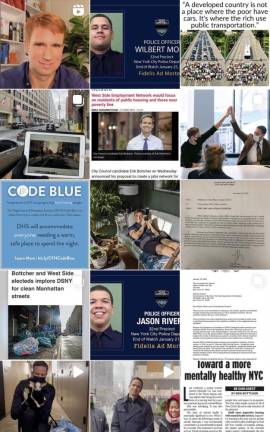

New Council Member Erik Bottcher’s Instagram page appears, as of late, to be filled mostly with screenshots of news stories covering his political endeavors, of photos and videos documenting life on the job.

Look a little closer, and you’ll find glimpses of family gatherings, videos of dance routines and self-recorded footage of Bottcher sitting on a sofa, being licked by a small pug (which is not his own canine companion, he notes in one caption, but makes a cute social media co-star nonetheless). “We have to make politics and government accessible and fun,” Bottcher said. “I’m just an open book.”

On January 24, Bottcher was selected to co-chair City Council’s Manhattan Delegation, a duty he’ll share with fellow Council Member Christopher Marte. As Council Member to District 3, which spans from West SoHo through Chelsea and to the southernmost part of the Upper West Side, Bottcher has big goals: For one, he’d like to boost the city’s recovery post-COVID-19, in part by cleaning up streets and sidewalks — literally. “It’s more than an aesthetic issue,” Bottcher said on the topic of sanitation.

But beyond the overtly physical and tangible, one of his primary targets for bettering the city is addressing mental health needs. It’s a task he approaches with unique insight and transparency.

“Care That Very Few People Get”

After the subway killing in Times Square on January 15 of Michelle Go by a man likely suffering from mental illness, according to multiple reports, Bottcher recirculated his mental health plan. In his outline of eight steps that he believes could help those in desperate need of care, Bottcher cites facts and figures. But he begins with an anecdote — one relating to his own experience of being “involuntarily committed to a mental health hospital for a month,” he wrote, following multiple suicide attempts when he was a teen.

“I got the care and support that I needed, that saved my life and that got me through that difficult time,” Bottcher said. “But sadly, that’s care that very few people get in this country.”

In New York, nearly one in 25 people live with “serious mental illness,” according to the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health, with certain populations — those without health insurance as well as Black, Lantinx, and Asian American and Pacific Islander New Yorkers — less likely to receive care.

Bottcher’s plan includes reversing the current decline in inpatient psychiatric beds (the number of which has dropped 12 percent in the state from 2000 to 2018, according to the New York State Nurses Association); expanding former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s 2020 pilot program of dispatching health professionals in response to mental health crises; and funneling more New York State public school funding toward mental health counseling resources for young people, to name only a few of the items on his agenda.

The Clubhouse Model

Change might also come from bolstering organizations already working to provide aid. Fountain House, a Hell’s Kitchen nonprofit started in 1948, kickstarted the “clubhouse model,” a form of care for those with severe mental illness that Bottcher would like to see replicated and supported further in all five boroughs. “People with serious mental illness, they don’t have anywhere to go,” Bottcher said. “We expect them just to stay in their rooms all day. They need a place to go where they can be part of a community.”

The clubhouse model, according to Chief Research and Knowledge Officer Josh Seidman, matches “members,” or those partaking in the model, with jobs in different “work units” within the house, ranging from clerical to culinary work. Fountain House currently sees between 1,200 and 1,500 regular members between its two locations in Hell’s Kitchen and the Bronx and its approach has been replicated at over 200 locations countrywide. “It helps people to feel that there is a need for them,” Seidman said, “and that they can contribute value.”

Former Fountain House President and CEO Dr. Ashwin Vasan was appointed in December by Mayor Eric Adams to become the city’s new Commissioner of Health in March, a move that Seidman says bodes well for the future of tackling mental health citywide.

Interconnected Forces

Mental illness, of course, intersects with other urgent issues, too. At Fountain House, which also helps to provide housing for those in need, roughly 40 percent of members have a recent history of homelessness — but almost all are housed within one year of joining the program. Members are also twice as likely to be employed, according to Seidman.

Community Board 4 has long pushed for the New York City Department of Homeless Services to open a shelter for families with children, according to CB4 Chair Jeffrey LeFrancois, who believes an integrated approach to issues of such scale—like homelessness and mental illness — must be faced together, as a unified city.

“Now that we see ourselves really at crisis-level amounts of folks without homes on the street, of real mental health needs of everyday New Yorkers, it can’t all be coming from the same neighborhoods that have been providing those services for a long time,” LeFrancois said of support for those in need. “We need to think about how that can be spread out to meet the greater needs of the city.”

In only the first few weeks of his term as Council Member, Bottcher’s already teamed up with a number of fellow elected officials. He spoke about the “intertwined” nature of the issues of mental health and substance use disorder at a January 25 press conference for the Comprehensive Addiction Resources Emergency (CARE) Act, reintroduced by Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney and others in December. He penned a letter with new Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine and several other local politicians to Mayor Eric Adams and New York City Department of Sanitation Commissioner Edward Grayson beseeching an increase in corner wastebasket pickups, residential street sweepings and curbside composting.

Many of Bottcher’s dreams — for instance, he believes we just might be able to “end mental illness in our lifetime” — will take exactly that: time. An admirer of reinvention, he looks to his late grandmother, who lived to be 104 years old, as a source of inspiration in his work today. “None of the progress that happened when my grandmother was alive — none of that just happened automatically,” he said. “People fought for it, they pushed for it. They organized, they innovated. They demanded change and that’s what we must do.”

If Bottcher succeeds, District 3 likely won’t look the same as it does now, even just a few years down the line.

“I got the care and support that I needed, that saved my life and that got me through that difficult time. But sadly, that’s care that very few people get in this country.” Council Member Erik Bottcher