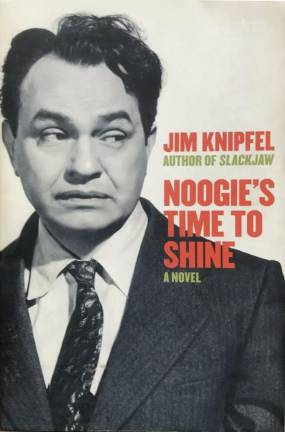

Jim Knipfel: Tapping the Source of the New Indie Film, Noogie’s Time To Shine

The legendary former New York Press journalist and writer— who is also legendarily blind—tells how his 2007 crime novel became a movie anyone can now see or listen to.

For decades, Jim Knipfel was one of the great New York City street journalists, ranking as a stylist with Djuna Barnes, Meyer Berger, Jim Dwyer, C.J. Sullivan— people like that. At the same time, Knipfel was also losing his eyesight from retinitis pigmentosa and while he’s now blind as Tiresias, with assistive technology, he remains a great, insightful, often hilarious writer on many subjects: literature, music, film, philosophy, cats, blindness, beer, cigarettes, more. See Knipfel’s Patreon account for details.

Knipfel is also the author of three acclaimed memoirs, one short story collection, and four novels, the second of which, “Noogie’s Time To Shine” (2007) is now a remarkable motion picture.

Co-directed by Austin, Texas, filmmakers Erik Horn and Bradley Perrett, Noogie had its local premiere in March. Presently viewable on Vimeo (https://vimeo.com/894583417), further screenings and streaming options— with accessibility features for the blind— are coming soon.

“Noogie” is really a movie! Can you believe it?

Yes, I’m tickled that “Noogie” is now reality, and turned out to be funnier and snazzier than I could’ve hoped. And it only took ten years.

I was always dead set against the idea of film adaptations of any of my books, especially the memoirs. It’s not that I was so precious about the books, but because I knew that whoever made it would royally screw it up. Of course, the minute a producer showed up and began waving a check at me, all those principles went out the window. I rationalized that taking that check for my first book, Slackjaw—this would’ve been 1999 or 2000—wasn’t a mortal sin because I knew there was a 99 percent chance it would never get made.

I was right about that, which was a relief, but the whole experience, dealing with Hollywood types, was such a nightmare I vowed never again.

A few years later I was contacted by a young Austin-based indie filmmaker named Erik Horn. He had no money and was looking to make his first feature. He was smart, he got Noogie’s jokes and obscure movie references, so by my standards he was perfect. We had a signed contract within two weeks, which may be some kind of record. I made it clear from the start that even though I wrote the book, it was their movie and they should turn it into whatever they wanted it to be. I was very hands-off. I had nothing to do with the script, the casting, anything. I trusted them, and it’s a decision I’ve never regretted.

Any thoughts on the process now that it’s done?

It’s been a nutso ten years since work on the movie first got underway, and I found myself doing things I never could’ve imagined I’d be doing. Why four kids in their twenties—Erik and the core crew—would insist that a blind, cranky fifty-year-old drunk join them on a madcap road trip from Miami to NYC to get some second unit shots is beyond me.

The whole production was very punk rock, straight out of the Roger Corman school of no budget filmmaking, which is precisely how Noogie needed to be made. It was a guerrilla production, stealing a lot of shots around the East Village and everywhere else. We even drove the van through the Halloween Parade, which was a psychedelic experience. A lot of that ended up in the movie.

Tell us about the genesis of “Noogie.”

On January 2nd 2002, there was a 250-word squib buried inside the New York Post. Beautifully constructed story, but in a nutshell it concerned a former NYU film student named Michael Schwartz. He was living in Jersey City and working as an ATM maintenance man, mostly in Manhattan. At some point he discovered he could siphon off a $20 bill here, a $20 bill there, as he was restocking machines, and no one would be the wiser.

By the time the accountants at the company he worked for finally did get wise, he’d amassed over five million dollars, all in twenties, which he kept in laundry bags in his closet. When he learned the company was onto his slow-motion heist, he grabbed the laundry bags and his two cats— who were of course named Bonnie and Clyde—threw everything in his van and took off.

This was late November 2001 and the city was still reeling after the towers came down, so no one noticed. He vanished for a month. Nobody to this day knows what he was up to during those weeks. He was found dead in a rooming house in Florida on Christmas Day. He’d apparently drank himself to death, and the money was nowhere to be found.

It struck me immediately that this was a real-life pulp novel, so I ran with it. It’s fiction, the names are changed and I had to Invent what he was up to that month he was on the lam, but for the most part Noogie was a pretty straightforward account. I even had to tone down a few things because elements of the real story were just too outlandish.

Funny thing is, when my agent started pitching it around, a bunch of editors passed because they thought the premise was too implausible.

For a variety of reasons, you again live in your native Green Bay, Wisconsin. Any thoughts on your exile from the city?

“Exile” is the correct term. In the summer of ’21, when COVID was still the defining factor of our daily lives, I got the bum’s rush from my second future ex-wife. I couldn’t afford Brooklyn on my own anymore, let alone Manhattan so I very reluctantly landed back in Nowheresville, where at least things remain stupidly cheap. It’s far from ideal and never part of the plan, but we deal, right?

I’d spent most of my life in New York, and it was the only place I’d ever sincerely considered “home.” Not a day goes by that I don’t miss it.

Know what I miss most about it? I’m reminded of this every day. People who don’t live there don’t believe me when I tell them New York is the best city in the world if you’re blind. Using only the sidewalks and the subway I could go anywhere I wanted solo. I didn’t have to depend on much of anyone save for the occasional kind stranger, and they were always easy to come by. I don’t care what anyone says, the NYC subway system is aces in my book.

Hundreds of thousands of Manhattanites will have the opportunity to read this in honest-to-Ganesh newsprint. Any message you’d like to share with them before they wash their ink-smudged hands?

Cherish those papers and ink smudges. Hold onto them. With most everyone around you experiencing the world from a safe distance through the alienating buffer of a screen, papers like this are among the rare few things that still anchor us to the real physical world and objective reality. The same is true for street-level local reporting.

These days Green Bay has a single daily paper. A few years ago it was sold to a nationwide corporate newspaper conglomerate. This once-decent paper now runs eight pages and features all the same stories you’ll find in USA Today, stories a cabal of businessmen decided were worth running.

A year ago two guys here launched an indie print weekly with nothing but local and neighborhood news, and it’s going gangbusters. So it seems there are still people out there—and if you’re reading this you’re one of them—who refuse to live, as most people do, in a Philip K. Dick novel. Not one of the better ones either.