As a burst of oversized and out-of-scale development projects radiate from the path of the Second Avenue Subway, a preservation group is fighting back — by publishing a book to document the area’s glorious past.

The Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts is delving into the boundless historical, cultural, architectural, mercantile and ecclesiastical treasures of Yorkville — at a time that heritage seems most in jeopardy.

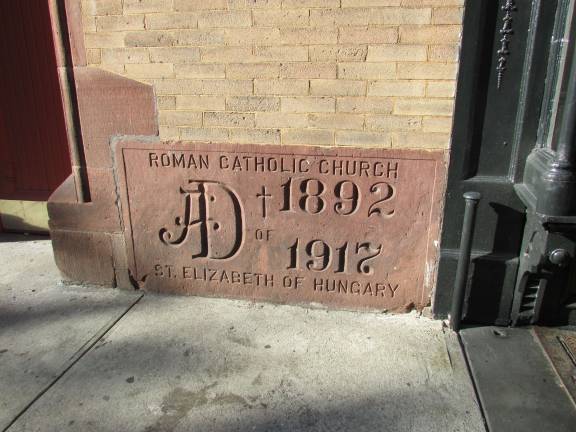

“Shaped by Immigrants: A History of Yorkville” plumbs the Old World roots of a neighborhood where Czechs, Slovaks, Germans, Hungarians and Irish lived and worked, dined and courted, shopped and prayed.

It salutes the immigrant ethos that made the community great and defines its character to this day — even though no one calls 79th Street “Goulash Avenue” anymore, or 86th Street the “German Broadway.”

Against the backdrop of a built environment that has largely endured for 150-plus years, the book raises several existential questions:

What hath the Q train wrought?

And how can Yorkville’s immigrant past — which lives on in its low-rise, small-scale buildings, serving residential, religious, commercial, social and recreational needs — be safeguarded amid a building boom?

In the foreword, Franny Eberhart, president of Friends of the UES, says now that the subway is here, and travel to and from Yorkville is faster than ever, the word most commonly used to describe the Q is “transformative.”

“But what other sorts of transformation will occur?” she asks. “And what might Yorkville lose in the process? What needs to be protected, preserved and celebrated?”

The book, and a 15-minute, mini-documentary film accompanying it, is an attempt to answer those questions by detailing a neighborhood’s brick and mortar, character and charm.

Drawing on over a decade of research, the advocacy group authored what it bills as the first-ever comprehensive history of Yorkville, an illustrated account replete with archival images and contemporary photos commissioned for the project.

“Numerous out-of-scale developments, many that subvert long-established zoning rules meant to encourage predictable development, are changing the face of Yorkville,” said Rachel Levy, executive director of the Friends group.

With its vitality and uniqueness threatened, “Shaped by Immigrants” celebrates the rich legacy of its architecture and peoples. The goal: “Kickstart the public conversation about the buildings and sites that must be prioritized for preservation amid rapid change,” Levy added.

The book features such long-vanished worlds as George Ehret’s Hell Gate Brewery, located on a superblock between 92nd and 93rd Streets and Second and Third Avenues and dating to 1866. It conjures up the German immigrant known as the “King of the Beer Corners” because his 42 saloons were mostly located on corner lots.

But it largely focuses on the extant. In so doing, it documents dozens of architectural gems that lack city landmark status and could theoretically fall prey to the hyper-development unleashed by the subway’s opening.

THE MAYOR AND THE ‘ ANTEDILUVIAN MONSTER’These gems include the “French Flats” apartment buildings, a term evoking Parisian living accommodations, which were designed for middle-class families at a time when the rich mostly lived in private, single-family homes, while the poor dwelled in multi-unit tenements.

Two of the best examples are on Second Avenue in the 80s. Counted among the city’s first modern apartments, they came complete with such then-luxuries as hallways, private bathrooms, closets and fully equipped kitchens.

The Manhattan, built in 1880 on 86th Street, and the colorfully named “Kaiser and The Rhine,” built in 1887 on 89th Street, were both ventures of the Rhinelander family, an early Yorkville developer, who designed them with more light and air than other period dwellings.

It was The Manhattan where future three-term Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. spent his childhood. His father, the powerful German-born U.S. Sen. Robert F. Wagner Sr., resided there from 1912 to 1933.

Upper East Side City Council Member Ben Kallos provided partial funding – $35,000 in the current fiscal year, $45,000 in the last fiscal year – for both the book and the documentary that accompanies it.

A lifetime Yorkville resident, he first moved to the neighborhood when he was just four years old, and three generations of the Kallos family have resided in the area.

The book pegs the evolution of Yorkville to five supersized, mass-transit projects — the building of two rail lines in the late 19th century, their demolition in the mid-20th century, and the arrival of a new subway in the 21st century.

Development was kicked into overdrive with the opening in 1878 of the coal-powered Third Avenue Elevated Railway, with stations at 67th, 76th, 84th, 89th and 99th Streets. By 1880, the Second Avenue El debuted, with stops at 65th, 72nd, 80th, 86th, 92nd and 99th Streets.

The impact of the locomotives: “A frenzy of real estate speculation,” a passage for immigrants away from the teeming Lower East Side and the growth of multicultural, working- and middle-class communities, the authors write.

Of course, the Friends group — a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the architectural legacy, livability and sense of place of the UES — notes that not everyone was overjoyed by the hulking Els.

It quotes social novelist Henry James describing them as “skeletons” whose streets they “darkened and smothered with the immeasurable spinal column and myriad clutching paws of an antediluvian monster.”

By 1942, as World War II raged, the city fathers (yes, they were all men back then) agreed. The Second Avenue El came down first, its steel converted to munitions. By 1955, the Third Avenue El was finally demolished.

“The dismantling of these lines removed the literal and figurative dividing line that had for so long separated the Gold Coast from Yorkville, while also ushering in a new era of building,” the book says.

Now, after three-quarters of a century, the trains are running again on Second Avenue. Commuters have direct access to and from Yorkville. The transformative impact to which Eberhart alludes is unmissable.

“We’re not going to stop development,” she said. “But I certainly hope we can preserve the flavoring and seasoning of the neighborhood, a great deal of which has already been lost.”

Father John Kamas, pastor of the Church of St. Jean Baptiste on East 76th Street, says he lived through the last “land grab.” Born in 1948, a lifelong Yorkville resident of Slovak descent, he remembers what happened when the Third Avenue El came down:

“You lost a neighborhood where people would hang out on the stoops, leave the front door unlocked and shop in the little shops under the El,” said Father Kamas, a Friends board member.

“That life started to disappear because real estate interests only see money, they don’t see neighborhoods, they don’t see history, they don’t see our immigrant past, they don’t see beauty,” he added. “We’re not opposed to growth, but it should be harmonious.

“This time, we’re asking developers to show a little more respect.”

“Shaped by Immigrants: A History of Yorkville” can be purchased online for $30 at www.friends-ues.org/yorkvillebook. A 15-minute, mini-documentary chronicling the neighborhood’s history can be viewed for free at the same link.

invreporter@strausnews.com