Time travel back to a New York just recently past—or to a long-ago past, when the horse-drawn omnibus served as public transport and pigs roamed the Bowery and ate garbage, the city’s first waste management system.

The New-York Historical Society (N-YHS) is offering visitors an expansive look at the ever-changing metropolis with the exhibit “Lost New York,” a story of transformation told through the lens of paintings, prints, photos, archival material and objects from the permanent collection. Voices of the people who live and work here accompany the items and give them new life.

A quote from William Faulkner, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” kicks off the show and situates visitors in the present as they look to the past and remember, be it Klein’s department store at Union Square with its on-site child minders or Keith Haring’s Pop Shop in SoHo.

Wendy Ikemoto, vice president and chief curator of N-YHS, spent some two years culling material for this fascinating display, inspired by the acquisition of two Richard Haas paintings depicting 42nd Street from the same vantage point at two very different times, 140 years apart.

One presents an 1855 view of Manhattan looking southward at the Crystal Palace (built for the 1853 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations) and the adjacent Croton Reservoir, while the other jumps ahead to the 1990s to offer an elevated view of Bryant Park and the New York Public Library, which occupy those same sites today, respectively.

“To me, that pair of paintings performs the concept of the show, which is the loss of a view, the loss of a certain New York. That’s what really made the idea crystallize,” Ikemoto said in an interview. The spacious first-floor gallery is replete with memories of bygone days, a New York with El trains, river bathhouses, East River swimming, high wheel bicycles (“Penny Farthings”) and fine dining at the 21 Club, with the late, great caricaturist Al Hirschfeld seated at the bar and recording the scene.

The high wheel bicycle, dating from 1883, is among the first items to greet visitors. It was a common mode of transport, albeit a risky one, in the late 1800s. The name, Penny Farthing, derives from the size difference between the two wheels, akin to the difference between a large penny and a farthing, a small British coin.

“That’s been a real draw for audiences because it’s so unusual,” Ikemoto said of the bike, believed to be on exhibit here for the first time. She related the story of a visitor who is a member of the New York City Unicycle Club “who explained to me that she could not test drive a Penny Farthing because she’s too short. You don’t think about those things unless you hear from someone who’s interested in vintage bicycles. The wheel is so large that you have to have very long legs and be very tall to ride it.”

River swimming on hot summer days, before the advent of air-conditioning, presented New Yorkers with its own set of perils. As the curator said about community feedback for this section of the show, “One woman was telling me about how she would go swimming in the East River and the older kids would jump in first to clear the oil from the water, so the younger kids could swim in it.” Reginald Marsh sets the scene with his painting, “East River” (ca. 1951), with five adults in the foreground enjoying free waterfront larks, while a steamship cruises by, a pastime generally reserved for the affluent.

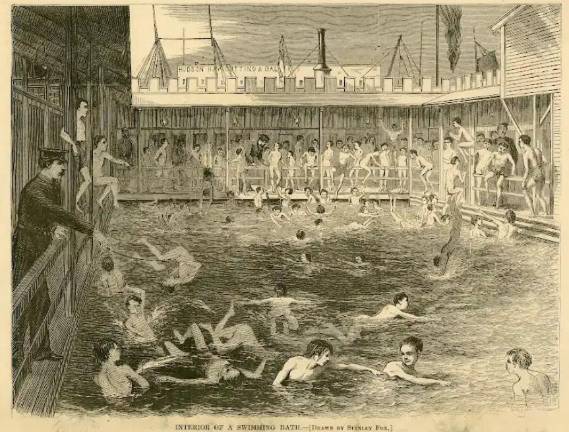

In the late 19th century, New Yorkers living in overcrowded quarters were mandated, for hygienic purposes, to visit river bathhouses (forerunners of public pools), described here as “floating structures with a central well sunk into the river water” and promoted as a safer alternative to river swimming. Several handsome wood engravings from the early 1870s and a small diorama paint the picture.

Harper’s Weekly noted that the first two river houses, on Thirteenth Street and the Hudson and on Fifth Street and the East River, were open in the evenings for bathing by gaslight. Another grouping pairs the Old Met Opera House on Broadway and 39th Street with the first Chinese-language theater on the East Coast in Chinatown, both opening in 1883 but serving a different clientele. The former, in an Italian Renaissance Revival building which opened to rival the established Academy of Music, has resonated with some visitors “because they remember the Old Met Opera House before it was demolished in 1967,” the curator said.

“A couple of people told me about their Long Island high school having a box for select students to use every week during opera season. And it has also resonated with our visitors because of ‘The Gilded Age’ HBO show. The second season centers around the old money/new money drama, which was really a battle between the Academy of Music and the Old Met Opera House.”

The Chinese Theater (see Stafford Northcote’s “Hi Hee, Chinese Theatre, Pell St., New York City,” 1899) hosted Cantonese opera performances, a mix of song, music, acrobatic acts and martial arts. In 1903, two decades after the Chinese Exclusion Act, the theater organized a fundraiser to help victims of a pogrom in Russia.

Per the curator, “We have two wonderful community quotes about that theater, and one is from the niece of Dek Foon, who is one of the co-organizers of a benefit performance at the theater to raise money to help Jewish victims of the Kishinev massacre.

And it’s just sort of amazing to hear that direct connection to somebody who is putting on one of these performances in the wake of the Chinese Exclusion Act, facing racism against his own community, to support others suffering from bigotry around the world.

The community voices initiative at NYHS began with an earlier exhibit and elevates the experience of the current one. The stories from New Yorkers “seemed so fitting because people remember these places and that is how they live on,” Ikemoto concluded. “So the exhibition is called ‘Lost New York,’ but all of these lost places are also recovered. They’re remembered through the artifacts we have on the walls and through the voices of the people who remember them.”