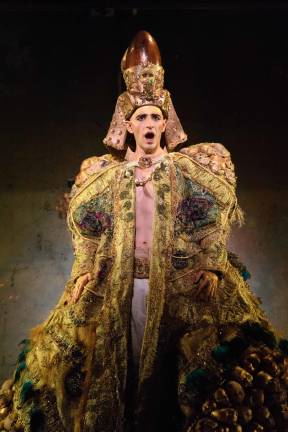

Playing the 'First Trans Icon'

Countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo on rehearsing for the Met Opera’s production of Philip Glass's “Akhnaten” – and the power of the human voice

Countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo is a trailblazer in classical music. Possessing a high, clear singing voice similar to that of a mezzo-soprano, Costanzo, 37, has brought his vocal gifts outside the traditional opera house to projects ranging from a music video with Tilda Swinton to a Kabuki play at the Minami-za Theater in Kyoto. As a collaborator with artists such as James Ivory, Luciano Pavarotti and Daniel Askill, he has pushed the boundaries of how audiences can experience classical music. This fall, he returns to the Met to perform the title role in Philip Glass's “Akhnaten,” an opera about a pharaoh whom Costanzo calls the “first trans icon.” We sat down with Costanzo to discuss rehearsals, modern notions of gender - and the full body wax he underwent for this role.

How did this production of “Akhnaten” come about? What attracted you to the material?

I had been doing a lot of Baroque opera, and I've done a lot of contemporary opera. That's sort of how the countertenor repertoire is divided, because we're before 1750 and after 1950 kind of people. I had not really encountered any opportunity to perform Philip Glass. But I loved “Einstein on the Beach” when I'd seen it. My manager, Caroline Woodfield, was really smart and said, "there is one opera that Philip Glass wrote for a countertenor, ‘Akhnaten.’ And it's a wonderful piece. And if anyone ever does it, you should consider it."

The English National Opera was doing it and offered me the role. I was really excited about it. Not only because musically it's an incredible piece in that it's the third of Philip Glass's so called trilogy operas that profile great thinkers. It is structured in a way that's incredibly theatrical. It allows for great emotional expression. And it's just beautiful music. But also the subject: this ancient Egyptian pharaoh who was perhaps the first monotheist, who stepped outside of tradition. Hundreds of years of one way of doing things, and changed it all. United upper and lower Egypt. Changed the way art was made, and writing was done. Had all of these very, very new, progressive ideas. And for 17 years, he implemented them. And then he was killed, and all of his ideas were reversed. So this idea, in our time today, of a ruler who’s very progressive and trying to change things and then the tradition and the more conservative factions pull him back is really interesting to explore.

What are some challenges you've faced in rehearsal for this production?

Philip Glass is not narrative in the conventional sense; it's not like a play where there's text telling you the story piece by piece. It's more of these abstract fragments of music and of antiquity. So the challenge became, how do you tell a story that engages an audience in a linear way throughout the evening? How to do that physically, but how not to work against the wonderful abstraction and beauty of the material. So we had to find a way to create a kind of stage ritual that would also be incredibly engaging for an audience. And I think what we wound up producing is unlike anything I've done in my career before.

For the previous Los Angeles Opera production of “Akhnaten,” you had to do a full body wax, as you appear nude in the show. What was that like?

It's very painful. It took like five hours. And yeah, we've done it all three times we've done the production. Egyptians were the ones who invented waxing. It feels almost like this sort of alien, this bald, hairless alien and/or child, which [Akhnaten] was. He was a teenager when he became king. And the nude scene is just as he's being crowned pharaoh. I realize all these extreme things that they were asking for had a real purpose. So that's why it felt like the right thing to do. And even if I don't feel like myself when I am going to the grocery store, I really feel like this character when I step onto the stage.

And the nude scene is your first scene on the stage, right? Is that terrifying?

Oh, yeah. Definitely. They always say that you should imagine the audience naked, but this is the reverse; everyone else is fully clothed.

You have called Akhnaten the first trans icon. What lessons do you hope today's LGBTQIA+ community takes away from this production?

I guess what I like about being a countertenor, and it's also embodied in this piece, is it breaks down a little bit our notions of pitch and gender. Generally, we think the high voice is feminine. But that's a very modern construct. The [modern] idea is that feminine is somehow weaker, and if we were going to display a man of power, we would display him with a low voice. But that power here comes from the combination of masculine and feminine. And not just one attribute being ascribed to one gender. But rather this very fluid and complicated construction of it that has been a part of the world for all of antiquity.

And for Akhnaten to have been the person, so they say, to have invented monotheism before Moses. Freud looks at him as the father of all Western religion, from Islam to Judaism and Christianity. And for that person to have been in some ways queer, by our standards today, I think is a powerful message in itself.

You do a lot of outreach performances in the Bronx with young school children. Why is this work important to you?

Music has a real ability to affect kids' lives, and I've seen that firsthand. Opera in particular is very primal, because it's the human voice; it's something we all have. A lot of the kids I work with have difficulties expressing emotion or connecting to something that expresses emotion. What's wonderful about art is that it gives you a little bit of distance with which to interact with these heavy, serious themes that you may be experiencing in your own life. Conflicts like death, or love, all of that stuff. And having a way to experience it through the lens of beauty I think is very useful to these kids.

So many of them were able to connect to the emotion of it. And to do it with every class that I did it with, and to always have kids who cry, because they were so affected by it, was really powerful. It makes you realize how powerful this art form is, even if people don't know anything about it. The greatest misconception about opera is that it takes so much knowledge and so much studying to even understand [it]. But in fact, if you let go of those misconceptions, if these kids can connect to it, then I think it's much easier for everyone to connect than they think.

This interview has been edited and condensed for space.