Slow Down and Savor These Masterpieces of New York

The holidays offer plenty of jingle and sparkle, but a quieter form of thrill can be found in local museums.

New Yorkers all know the hustle and bustle of Rockefeller Center, Macy’s at Herald Square and the Fifth Avenue store fronts. Why not seek out a calming moment with a masterpiece that also captures the holiday spirit? Here are four that are definitely worth a visit.

Medieval Madonna

The Cloisters always dress up for the holidays with festive decorations composed of plants, sheaves of wheat, and beautiful vessels recalling Yuletides long ago. In the treasury downstairs there’s a sculpture of the Madonna and Child carved in the 1400s that is truly breathtaking. Don’t let its diminutive dimensions disarm you. Despite being only 13 inches tall, this work is as great as a towering Michelangelo, and it was as radical and influential in its day.

It was made in about 1470 by Niclaus Gerhaert von Leyden. The mastery of the carving boggles the mind, and the emotional impact of the pose redefined the medium. Just a few decades earlier, wooden sculptures looked—well—wooden. Stiff, frontal poses and flat expressions were the norm. Here, the infant Jesus tugs on Mary’s scarf while she embraces him protectively. See how her pressing fingers create little mounds in the soft baby flesh. Marvel at the draping of the fabric in her dress, the individual curls that tumble down her back and the crisscrossing ties that hold her cape, each string thinner than a strand of spaghetti, all carved out of a block of boxwood. There are wooden representations of cloth, in places thinner than actual cotton fabric, swirling in complex patterns around her body, enlivening the pose. One fold even dips precariously over the base, as though she’s about to take a step towards the viewer.

Why would a sculptor make something so difficult to pull off? Because he could, and he wanted everyone to know. The honey-toned wood, more valuable than gold in the hands of carver Niclaus Gerhaert von Leyden, makes this an unmissable, if often overlooked, masterpiece.

Peek into Manhattan of Yore

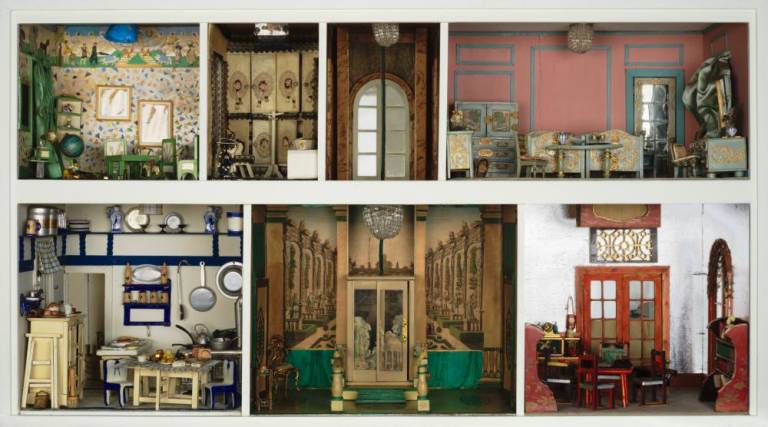

Giving a whole new meaning to the idea of “tiny homes” is the Stettheimer Dollhouse at the Museum of the City of New York. Some housecleaning was necessary before holiday guests arrive, and the museum just finished a major sprucing up as part of its centenary celebration. “The Stettheimer Dollhouse in a New Light” featuring the beloved, quirky, artful model of a chic New York home went back on view on November 22. With two floors and twelve rooms, an elevator and a sculpture garden packed into just over two feet high by four feet wide, it offers a glimpse into the luxurious world of an Upper East Side family in the early 20th century.

The meticulously fashioned portrait of a home was crafted over a period of twenty years by Carrie Stettheimer one of three daughters of the family. Her sisters were author, Ettie Stettheimer, and Florine Stettheimer, a noted painter. The family was known for hosting salons that included the leading artistic minds of the day, who’d often take a peek at how Carrie’s house was progressing. Some even contributed works of their own. Tiny paintings and sculptures were added by artists like Marcel Duchamp, Gaston Lachaise, and Marguerite Zorach. From the nursery to the kitchen to the tiny art gallery, it’s fun for young and old, completely without equal and only in New York.

4,000 Years of Jewish Culture and a Rare Stone

Sometimes it takes a moment to wrap your head around what you’re seeing. That may well be the case with the Tel Dan Stele. It’s a stone tablet –a fragment of a monument, actually—that was carved in the 9th century BCE. Some 3,000 years ago, artisans recording history with chisels literally wrote in stone the name of King David, and you can see it here. Outside of the Old Testament, this is the earliest documentary evidence of the house of David.

It’s on loan from the Israel Museum in Jerusalem from December 5 through January 5 and is included in “Engaging with History: Works from the Collection,” which brings works from Pop Art to antiquity together to celebrate more than 4,000 years of Jewish culture. Part of the exhibition is a focus on Hanukkah menorahs. In silver and gilt, lit for centuries and passed through families, or contemporary abstract creations in playful colors, they echo the warmth of the holiday.

Many Pictures, One Story

The Baroque Christmas tree at the Met always dazzles, so make your way through the crowd for a close look. Then, a trip upstairs to the European painting galleries offers another vision of the Nativity, this one as still as if it were frozen in amber. “Nativity with Donors and Saints Jerome and Leonard” was painted by Gerard David in about 1510-1515. It’s roughly the size of a picture window, and indeed it’s a window onto many things at once.

David, who was born in Oudewater in the Netherlands but practiced in Bruges, was one of the leading painters of his time, and the Met holds more of his work than any other collection in the world. They’re small jewels in pristine colors, full of quietude and grace.

In this piece David weaves together the wealth and refinement of the bustling port city with reverence and faithfulness to the story of Christ’s birth. Details abound and reward slow looking. Though it looks castle-like with its crenelated walls, the artist reassures us that the scene takes in a manger by including a thatched roof replete with holes. Angels float above, and an ox and donkey nestle close to the Holy Family. Shepherds peep in, taking a break from watching over their flocks scurrying up a hill. St. Jerome is there with his trusted lion. There’s a gorgeously painted basket—each bend of willow distinct—filled with swaddling cloths, and a sheaf of wheat, hinting at the bread of life. The donors who commissioned the work were entitled to a front row view of the miraculous event, as is the viewer. It’s a hushed, beautiful moment offering a point of reflection and a reminder of the sense of this story told over and over in art: from the most humble beginning all things are possible.