Writer Says He First Learned About Kindness in His Father’s Butcher Shop in Brooklyn

He’s a lawyer and a senior citizen nowadays, but the writer says he first learned about the value of kindness in his father’s butcher shop growing up in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn.

Kindness is in short supply these days. I miss it, but maybe as Ed Koch used to say, things were never the way they used to be. In any event, and without getting too political, kindness seems to be as rare as quality control in the Wuhan Wet Market. I don’t have the answer as to why, but I can tell you how I learned about kindness many years ago. It was from my father, who had a little butcher shop in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, which he had opened when he got back from World War 2. He made a living there. I learned about kindness there.

The shop had the usual counters, butcher blocks and showcases. It also had three stools in front of one of the cases. By the time I was old enough to notice them, their wooden seats had been painted black, but when the paint chipped, you could see the green and red and white that had come before. They were weathered. So was my father. He was only 36, but three years in the Pacific, malaria and a piece of shrapnel in his stomach can do that to a 31 year old, who prior to 1941, had never been farther away from Brooklyn than the Poconos.

On any given day, there might be one or more of the following individuals seated on those stools:

Vincent, the barber who had suffered a stroke and wasn’t able to cut hair.

Julio, the old stone mason who had suffered a back injury and now was only able to ”supervise.”

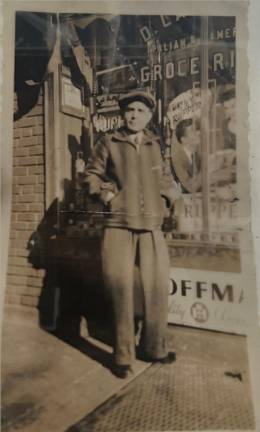

Abe, the grocery store owner from down the block, in whose pickle barrel I saw unidentified floating objects...hopefully they were pickles... as mysterious as the numbers tattooed on his forearm.

These weren’t the only ”guests” whose visits to the store had little to do with chuck chopped, but they were the ones I most remember. Today you might call them disabled, mentally or physically. In 1956 they were just people who seemed to have every right to come in, sit down and engage in conversation for an hour or so. My father was a very good listener, which in retrospect, was a large part of what they needed.

So what did I learn?

Well, I got my first haircut from Vincent (and many more after that) with his hands shaking and my heart pounding. So did my father, although I don’t know about the heart pounding. My father felt (and he didn’t have to say anything to let me know what he felt) that allowing Vincent to cut our hair made him feel competent, still needed, no less a man by virtue of his disability. If an ear got nicked occasionally, that was a small price to pay for the benefit it brought to Vincent.

Due to a back injury, Julio could no longer mix concrete or lift heavy stones, but my father sought his advice on a range of projects that I suspect both of them knew would never get started, let alone get finished. That wasn’t the point. It was using his experience, even when his back was beyond repair, that really mattered.

Then there was Abe. In many ways Abe was hard to look at as disabled. He owned the grocery store on the corner and when he walked (”strode” might be a better term) from the ”back,” as they called the area beyond the curtain, he seemed like the captain of a ship. His wife Sarah often manned the ”front,” as they called the area by the cash register, but it was Abe who did the ”public relations.”

”How’s you (sic) father?” he would ask when I came in for a container of milk. ”Tell him to take it easy.” It was always an adventure for an eight year old to enter Abe’s world. The shelves overflowing, the ladders and hooks and gadgets to get things on the higher shelves, and every inch of floor space filled with good things to eat. But there were those numbers tattooed on his forearm in blue ink. Even at eight I knew about tattoos, but not those tattoos. The kind I knew about were only gotten by sailors, in places like Shanghai. It was, as they say, a different time.

Once when I brought the milk back, I asked my father about those numbers. It was clear that I had touched on a subject that upset him. ”He’s a refugee,” he said, looking away. That was that. It was as if those numbers so pained my father that he just could not go there. All he could muster was ”If we need any groceries, you buy them from Abe. He’s a good man.” It was many years later... in high school I think...that I learned the I meaning of those numbers.

Very often you learn how important something is by the void, the sick aching feeling you get, when it is absent...and the lengths that someone will go to give that something to someone else. Well I know where I learned about kindness. Like some latter day trip down the yellow brick road, I had seen a man who needed to feel competent, and was given a chance to practice his trade; another man who needed to still feel useful, and was given the opportunity to use his brain rather than his back; and finally a man who needed to know that he still had a heart beating under that tattooed skin, even though so many had tried to take that from him.

I know who taught me about kindness, but who will teach our children and grandchildren about it? Maybe it doesn’t take a village. Maybe all it takes is a couple of stools, a willingness to listen and the empathy drawn from our own suffering, to help us engage in not so random acts of kindness.