“Coach Jake” Overcame Troubled Past to Become Winningest H.S. Soccer Coach in NYC History

Martin Jacobson, who has won 20 NYC championships with Martin Luther King Jr. High School, is aiming for another trophy this season. After defeating heroin addiction in the 1980s to become a beloved coach, he told Straus News that he’ll continue mentoring high school kids “until I can’t.”

Martin Jacobson, the beloved soccer coach of Amsterdam Avenue’s Martin Luther King Jr. High School, points out that “everything I do is a fight.”

Jacobson–who goes by “Coach Jake”–made the observation while describing his weekly battle to secure a public park for his team, which he has developed into a NYC powerhouse since he took over three decades ago. Its transition, from a rag-tag outfit to perennial 20-time championship material, clearly hasn’t made his quest for scarce Manhattan playing fields any easier. When they can’t obtain permission to play in the park, they practice on a slightly scuffed pitch that he’s secured for them behind the school’s cafeteria (with the help of UWS City Council Member Gale Brewer’s participatory budgeting funds).

After walking with Jacobson around the bustling lunchroom, where he is greeted with reverent daps from his young team, one can easily believe that few coaches are as highly admired or sought after as he is.

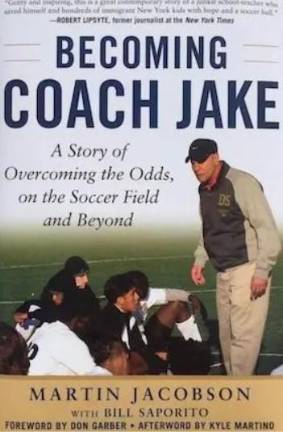

He’s been featured on the CBS show “60 Minutes” and wrote a memoir–with Bill Saporito–that was published by Simon & Shuster, “Becoming Coach Jake: A Story of Overcoming the Odds, on the Soccer Field and Beyond.”

In a truly riveting course of events, his coaching career began about a decade after he overcame a severe heroin addiction. Jacobson has said that he became hooked after an opioid injection on his 35th birthday, in 1981.

Throughout the intervening years, he fell into a black hole of scoring drugs, which could involve forging checks and trading pilfered goods. He briefly lived in New Mexico in the mid-80s, before going clean on a flight back to New York in November 1985. Jacobson said he hasn’t relapsed since. The legal aftermath of his struggles haunted him for a little while afterward; he managed to avoid a 30-year sentence stemming from an arrest warrant that trailed him from Santa Fe.

Jacobson was working as a guidance counselor when he took on the coaching gig at the then-winless MLK in 1994. He’s said that he fell in love with the game as a youngster, and in later years that passion has helped him keep a relapse at bay. It’s also allowed him to pass on his sporting wisdom to a wide host of brilliant young soccer tacticians that he actively recruits. Many are recent immigrants from the Caribbean, Latin America, and Africa.

When asked about what makes him so determined to win, he says that ”winning makes me feel like using, like the euphoria I would get.”

Jacobson has also kept Hepatitis C at bay, and just this summer, he had squamous cell carcinoma removed from his head–marking another foe that he hopes to fully vanquish this season.

During a sit-down conversation with Jacobson in his office–he serves as the school’s athletic director, alongside his fellow soccer coach Kimani Calnek–he expressed brief disappointment over a narrow loss in last year’s semifinals. He expects that his team’s fortunes will bounce back this year. Jacobson explains his recruitment strategy by referencing the classic baseball film Field of Dreams, emphasizing that “if you build it, they will come.” He adds that “coaches call me, they’ve known me for years.”

When Jacobson recruits players, he notes that “you call their mother and you meet them.” He then tells them “what our plan is. We have an educational plan. I have to graduate every kid, and I do.” His star players have gone on to have strikingly diverse and successful careers. A list of alumni, which Jacobson includes on the website for a foundation he runs, features former players working in everything from academia to carpentry.

Jacobson has a simple bit of advice for his graduating players: “I tell my kids, when you’re finished here, you go out and help others.”

He understands that he’s found some personal fame along the way, as he’s been the subject of various other documentaries and innumerable profiles. Coach Jake, one such documentary, can be found on Amazon Prime Video and Apple TV. Another memorable feature involves NBA star Carmelo Anthony interviewing Jacobson for VICE Media. Of course, he’s still proud of his memoir.

This doesn’t detract from his selfless devotion to his student athletes. Jacobson told Straus that’s he particularly excited about an upcoming miniseries produced for the Olympic Channel, We Are King, which will involve extensive footage of him leading his team to their most recent championship in 2022. Yet a trailer for the film reveals that it will be largely be oriented around the home lives of his young players, who leave it all on the pitch for their families.

It’s hard to imagine Jacobson would want it any other way. ”I’m going to get rewarded in soccer heaven,” he jokes. “I’ll probably get some minuses for some of my other behavior.”

“I’ve been pretty honored,” he continues. “I don’t yell at kids, I don’t scream at kids. They’re kids. That’s what we should all do as educators.” He does admit that winning so much has “changed the culture” of the school, at least somewhat, but that victory comes down to being a well-rounded individual.

His co-coach, Calnek, echoes the idea that winning is about more than just technical skill. After joining Jacobson’s interview with Straus during his lunch break, he says that “what makes the brain good is the heart. What makes the heart good is the spirit and the soul. We gotta get them to buy in.” Calnek adds that many players want to win the gold, given the glitz and the glamor of it, but that they need to know “why” they want to win–who they will help by doing so.

Or, as Jacobson puts it, “you really have to have love.”