A New Classical Penn Station? This Backer’s Plan Inspired by Grand Original

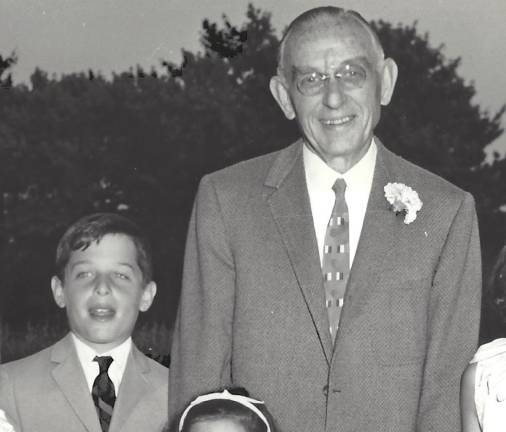

Tom D. Klingenstein, writer and philanthropist, recalls visiting the original Penn Station with his grandfather shortly before the majestic rail hub was demolished in 1963. He thinks President Trump can help restore it to its past grandeur.

Joseph Klingenstein must have known the architectural masterpiece was doomed when he took his grandson to see it.

Visiting the iconic locations of New York was a thing for Grandpa Joe and his grandson, Tom. The Statue of Liberty. The Empire State Building. Yankee Stadium. The Stock Exchange, which was particularly appropriate since Joseph Klingenstein was the co-founder of Wertheim & Co., the legendary investment firm.

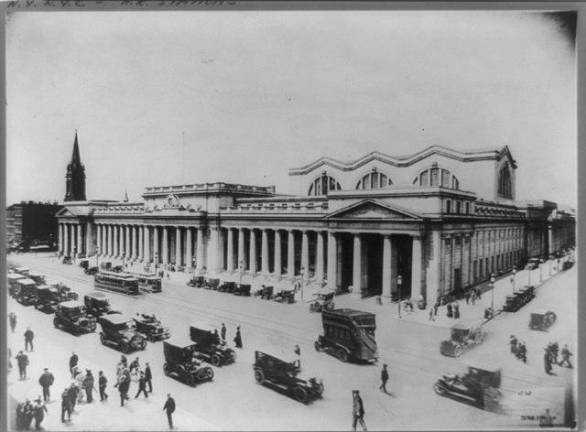

One of their stops was the McKim, Mead & White masterpiece, Pennsylvania Station, whose grandeur made a big impression on 10-year-old Tom.

“It is sort of awe-inspiring,” he recalled all these years later. “You were so small in such a big place. In that way it’s kind of humbling. But in another way, it’s kind of aspirational. It’s kind of like being at the Grand Canyon. Something of that size and magnitude is almost transcendent. It gets you closer to God, or whatever you think is transcendent.”

His visit with Grandpa was in 1963. Young Tom had no sense in that moment that the financial wheel was about to grind the grand station into rubble. But Joe Klingenstein, whose ability to follow markets and companies earned millions for himself, his family, and his clients, must have understood.

The year before, the financially fading Pennsylvania Railroad had announced it was selling the rights to build a sports arena atop its train station. It took a while for the import of this to sink in. But by 1963, architects and preservationists were protesting the planned destruction of the station.

“He was communicating to me this is something that’s really important and, indirectly, something that ought to be preserved like those other iconic places,” Tom, now 71, recalls of that visit to the last days of Penn Station.

Efforts to save the station failed, and young Tom watched it disappear.

“The demolition took a long while, it just didn’t happen in a day,” he recalled. “I saw it in ruins.”

The experience clearly stayed with him. Six decades later, Thomas D. Klingenstein, philanthropist, writer, benefactor of conservative causes, chair of the Claremont Institute, a think tank, is the driving force behind an ambitious plan to revive at least a version of that great station.

He contributed $3 million to a group called the Grand Penn Community Alliance, a grassroots organization that, after three years of work, recently unveiled its proposal to move that sports arena, Madison Square Garden, and build a new train hall bigger than Grand Central Terminal and echoing the architecture of the late lamented Pennsylvania Station.

Klingenstein says he was convinced he should get involved with Penn Station by a group he supports, The National Civic Art Society, which campaigns for a revival of classical architecture.

“The old Penn Station, the original of what we propose, is beautiful,” Klingenstein explains. “Some of it is beauty. Some of it—an important part—is our link to the past. Architecture, like our history, provides our link to the past, and the past is very important because it helps define who we are. It helps to guide us. It shows us models of excellence and models of whatever the opposite of excellence is. Particularly today when there is a tendency to want to tear down. I think it’s a time to build up.”

The Grand Penn Alliance proposal is one of four competing plans for the revival of Penn Station, which serves some 600,000 riders a day, most of them commuters, in cramped and unsafe conditions.

Klingenstein describes his plan as a “long shot,” but not quite as much of a long shot since Donald Trump returned to the White House.

“The president has expressed a real interest in resuscitating classical architecture. He’s a New Yorker and he’s also a deal maker. There are a lot of parties involved who need to be placated one way or another.”

Klingenstein wrote an essay for his own website on his work to revive Penn Station and headlined it: “Only Trump Can Make Penn Station Great Again.”

The President is, in a manner of speaking, also the landlord, since the remnants of Penn Station—that is, everything from street level down—are owned by Amtrak, the corporation that took over national passenger rail service from the failing Pennsylvania and other railroads. Amtrak’s only shareholder is the federal government.

Amtrak has, in turn, delegated to one of its tenants, the MTA, planning for the renovation of the present station. Gov. Kathy Hochul raves about that plan, which leaves Madison Square Garden in place. She says she has spoken to the President about it. He is interested, she suggested, although he “winced” at the price tag.

“Governor Hochul has come up with a plan that she says would fix Penn Station,” Klingenstein responds. “The plan, however, is mediocre, uninspired; frankly, it is depressing. New York City deserves much better.”

The Grand Penn Alliance says its plan, while more ambitious, would cost the same as the MTA/Amtrak plan, $7.5 billion. “Hochul’s plan is so expensive precisely because it requires working around the current Madison Square Garden,” Klingenstein says.

The two other proposals are from a private developer, ASTM, and from ReThinkNYC, an advocacy group. ReThink also wants to revive the classical construction of the original Penn, with or without moving the Garden, and ASTM proposed to leave the Garden in place but build an expansive train hall by tearing down the theater on the Eighth Avenue side of the Garden.

The President’s exact views are not known, but his administration has clearly engaged.

A spokesman for the Federal Railroad Administration, a part of the US Transportation Department, said the agency “is currently reviewing the Penn Station Capacity Expansion and Penn Station Reconstruction project proposals.”

The railroads had separated the question of reconstructing the station, with MTA in charge, from the planning for what Amtrak and New Jersey Transit, another tenant, say is a need to double the station’s capacity by the 2030s.

In its waning days, the Biden administration granted $72 million each for the planning of reconstruction and expansion.

“We expect to announce some news regarding this review in the coming weeks,” said the Railroad Administration spokesman.

Gov. Hochul has said she wants to press ahead now on improving the passenger experience without waiting for the capacity expansion. But the chief architect of the Grand Penn Alliance, Alexandros Washburn, has said it is more logical to consider them together.

The Grand Penn plan includes an expansion of the station to the south, something the railroads are believed to favor. But others, like ReThinkNYC have argued the destruction of all or part of the block to the south is unnecessary if the railroads will integrate their operations to run more trains through the present station. Gov. Hochul has said she will not “destroy a neighborhood.”

RethinkNYC’s Samuel Turvey has been pressing the railroads to use part of those $72 million grants to conduct an independent review of rail operations at Penn Station to see if capacity can be expanded to meet their goals without physically expanding the station.

Klingenstein says he is leaving the debate on train logistics to those with more expertise, focusing his attention on the opportunity to restore architectural history.

“We have an idea that ‘new’ tends to be better,” he said. “But I think we could in this case learn a little bit from the Europeans. This is one way to recover our past. This kind of architecture is our architecture. It’s American architecture. It’s a kind of physical expression of our political philosophy. Of the theory embedded in the Declaration [of Independence]. This is why all the great Washington buildings are classical. That was the medium of America. And I think that is worth recovering.”

Classical architecture is “American architecture. It’s a kind of physical expression of our political philosophy.” — Writer and philanthropist Tom Klingenstein